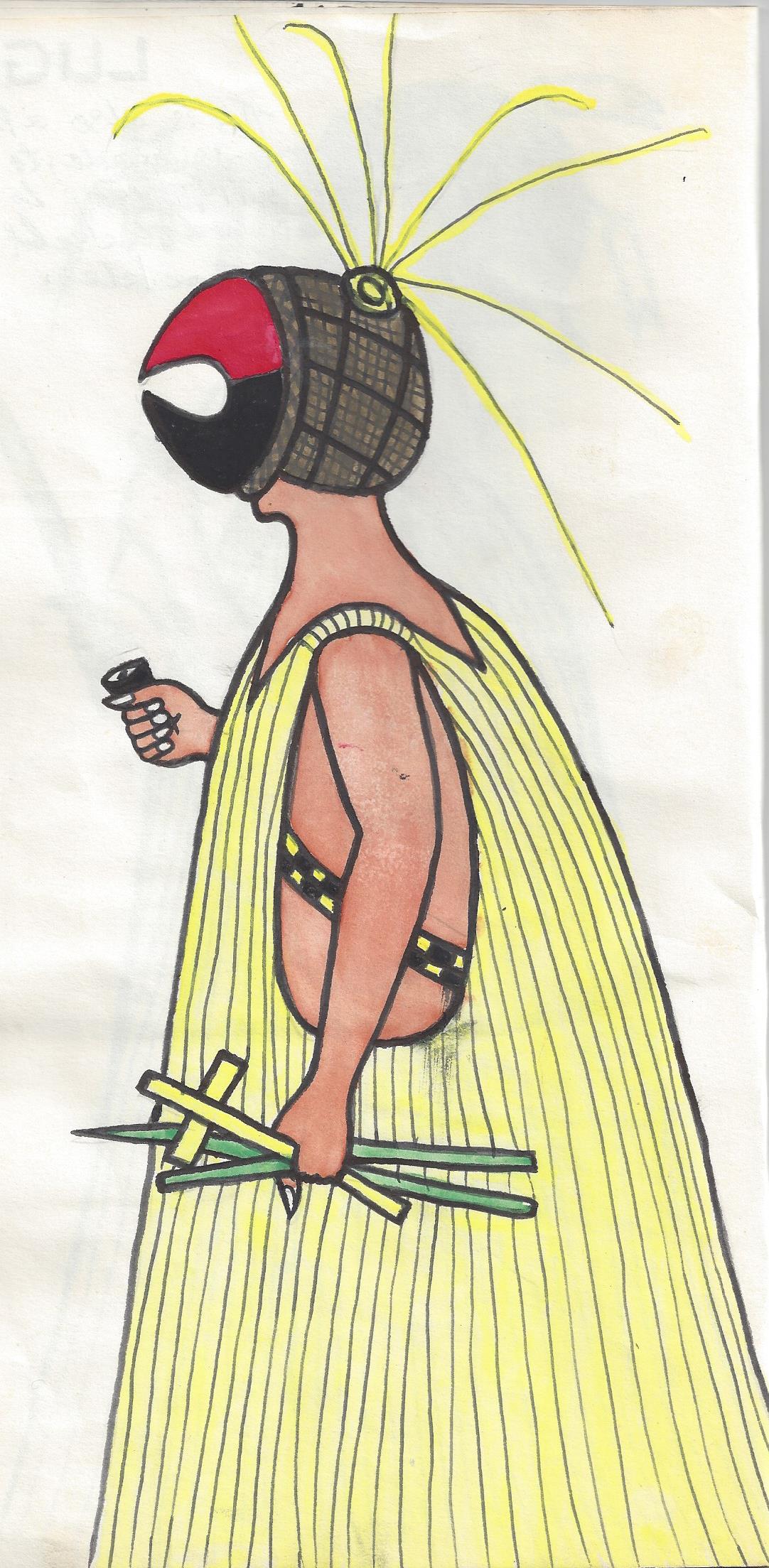

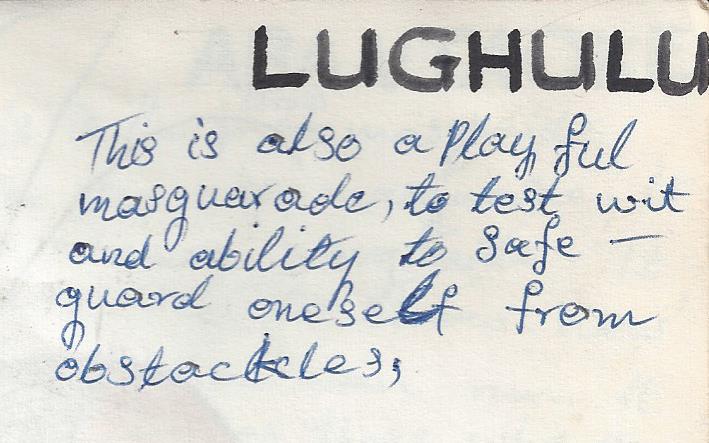

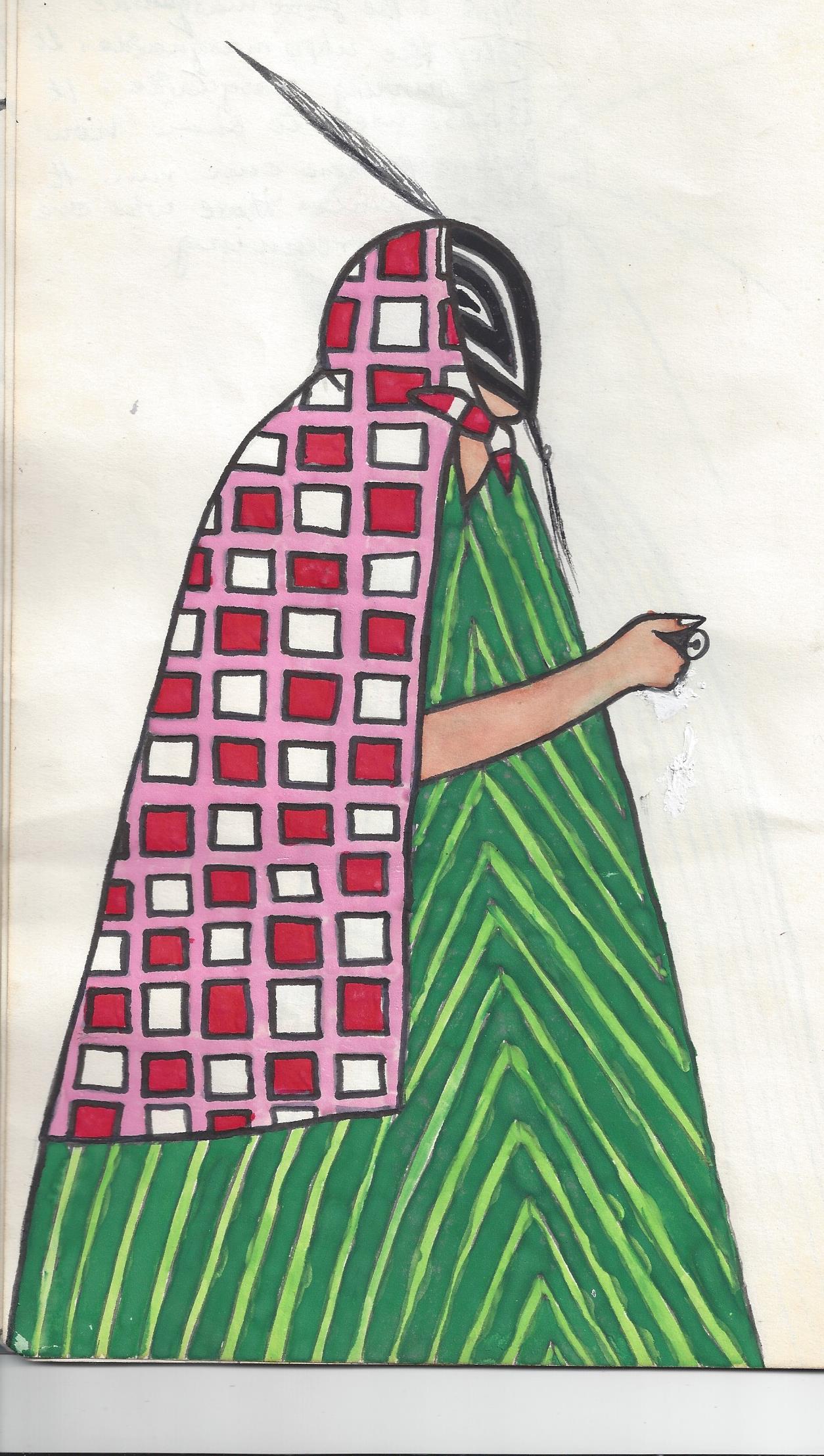

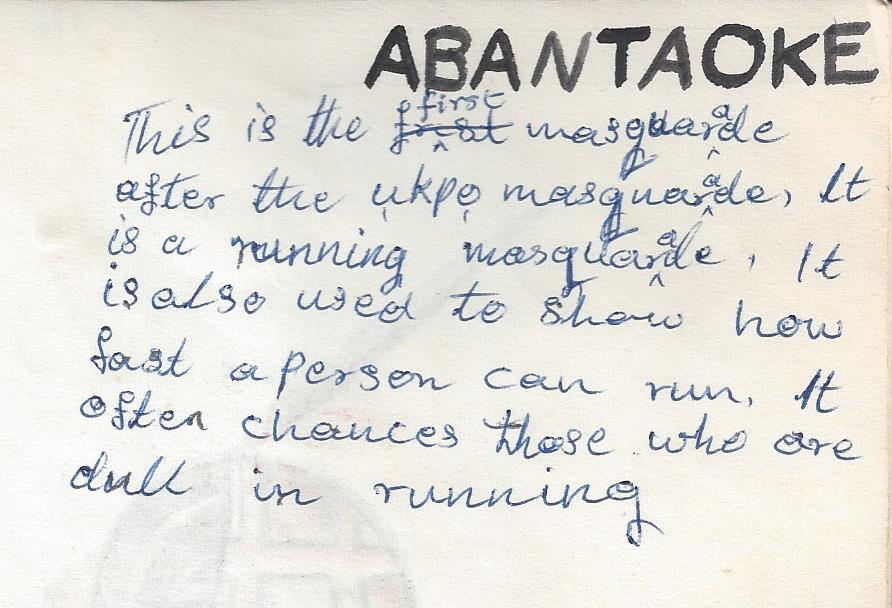

Paintings of Edda Masquerades

by Fidelis Orji Arua, 1966

I always looked forward to visiting Afikpo, which is far on the eastern edge of Igboland. I found it to be culturally rich, plus it had several carvers willing to carve and sell wonderful masks to outsiders, including us as Peace Corps Volunteers. This was not easily done in other areas of Igbo settlement. In Chapter Three, you can see examples of Afikpo area masks collected by other PCVs. My own collection is found in the Gallery.

There were a few PCVs stationed in the area, and they were helpful to me making contact with the abundant artists of the area. One was Jack Williamson, who was well trusted and familiar to so many in Afikpo town that they were not anxious about him. When Jack was taking the occasional photograph of the masqueraders, they were relaxed about it. This was not true for masqueraders, or villagers, for that matter, in other areas.

Somewhere, I have misplaced a slide carousel containing several of these rare images taken by Jack. I will post them on this website if I ever find them again. I did find one picture Jack took of a dazzling ring of dancers in Amaseri, the village adjacent to Afikpo town. This is by far the most intense masquerade picture I have ever seen from Nigeria. They are wearing the unique Amaseri variation of the famous yam knife mask. This picture is presented in Chapter Two. Yam knife masks of all kinds are to be seen in the Mask Section of the Gallery.

Afikpo, a big town in 1966, is also the regional name to include the culturally related villages of Amaseri, Okpoha, and Edda nearby. The Gallery shows a number of these fabulous masks from all these other places. The styles are similar to the neighbors but are produced in their own unique variations. I am not aware of any academic study comparing these styles, but they are fascinating to me. It is something I have attempted to contribute to this website.

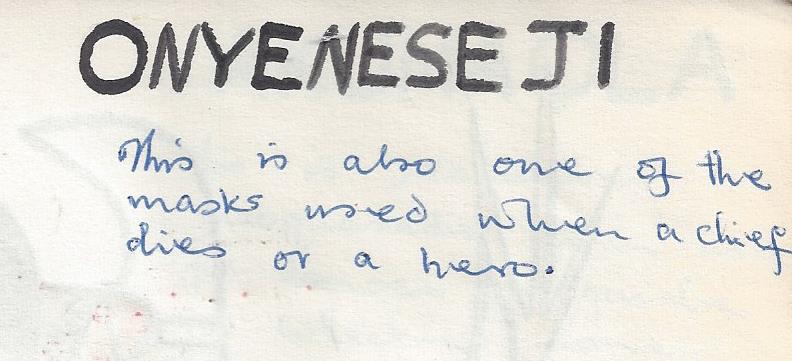

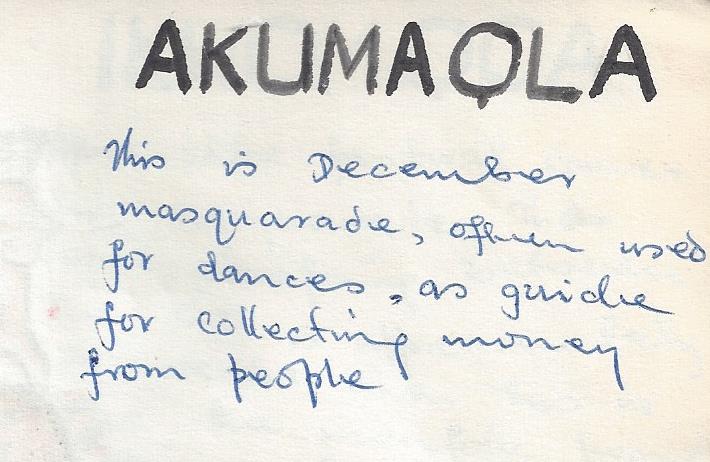

I never really knew when masquerades would appear in the related Afikpo villages. It was just by chance that I might visit on a day when they were playing. When I collected masks from the carvers, I attempted to gather the names of the masks and the celebrations in which they appeared. These are shown on the data page for each mask in the Gallery.

The lead scholar on the subject was Prof. Simon Ottenberg (recently deceased) from the University of Washington/Seattle. His profound books are listed in my Bibliography. He worked closely with the master carver Chukwu Okoro, whose workmanship and attention to detail rank among the best. I put him in the same class as Lamidi and Akin Fakeye, the Yoruba master carvers, Chief Idah of Benin, and Aka Gworo of Inyi. There were other quality carvers in Afikpo, such as Nnale Ejaw Okoro, but Chukwu Okoro stood above the others.

Being an outsider, I dare not attempt to take photographs of masquerades. As is true in all parts of Igboland, in 1966, masquerades were considered spirits and not acknowledged as villagers dressed up in costumes. Taking a picture of anyone was capturing their image, which they often viewed as capturing their soul. Many (not all) of the rural folk, were very afraid. When it came time to photograph the masquerades, the danger was that the viewer might later be able to recognize a familiar person by their stature and their movement. This would ruin the cover that was so protected by the secret men’s society that these were kinfolk in costumes, not real spirits. They were serious, and I was respectful.

One day, while I was visiting Afikpo, I met another PCV (not Jack) who shared with me some charming watercolor paintings of flowers. I was enchanted and asked to meet the artist. He turned out to be a teenager who had been educated through elementary school, so his English (Nigerian English) was understandable and his handwriting legible.

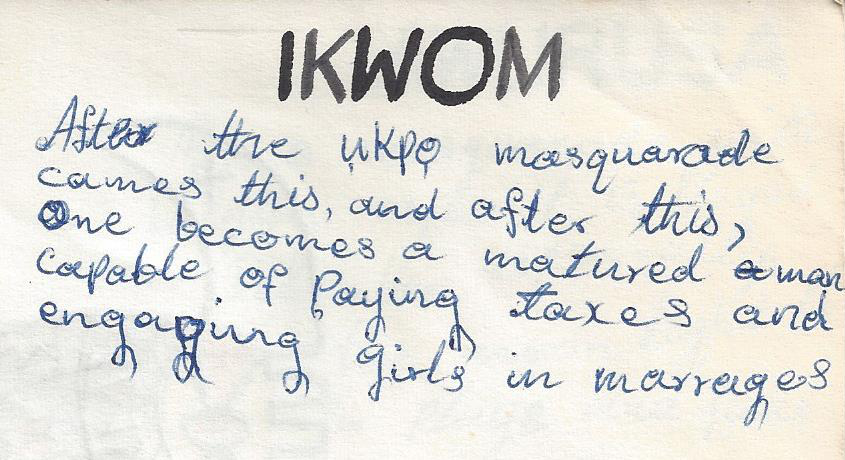

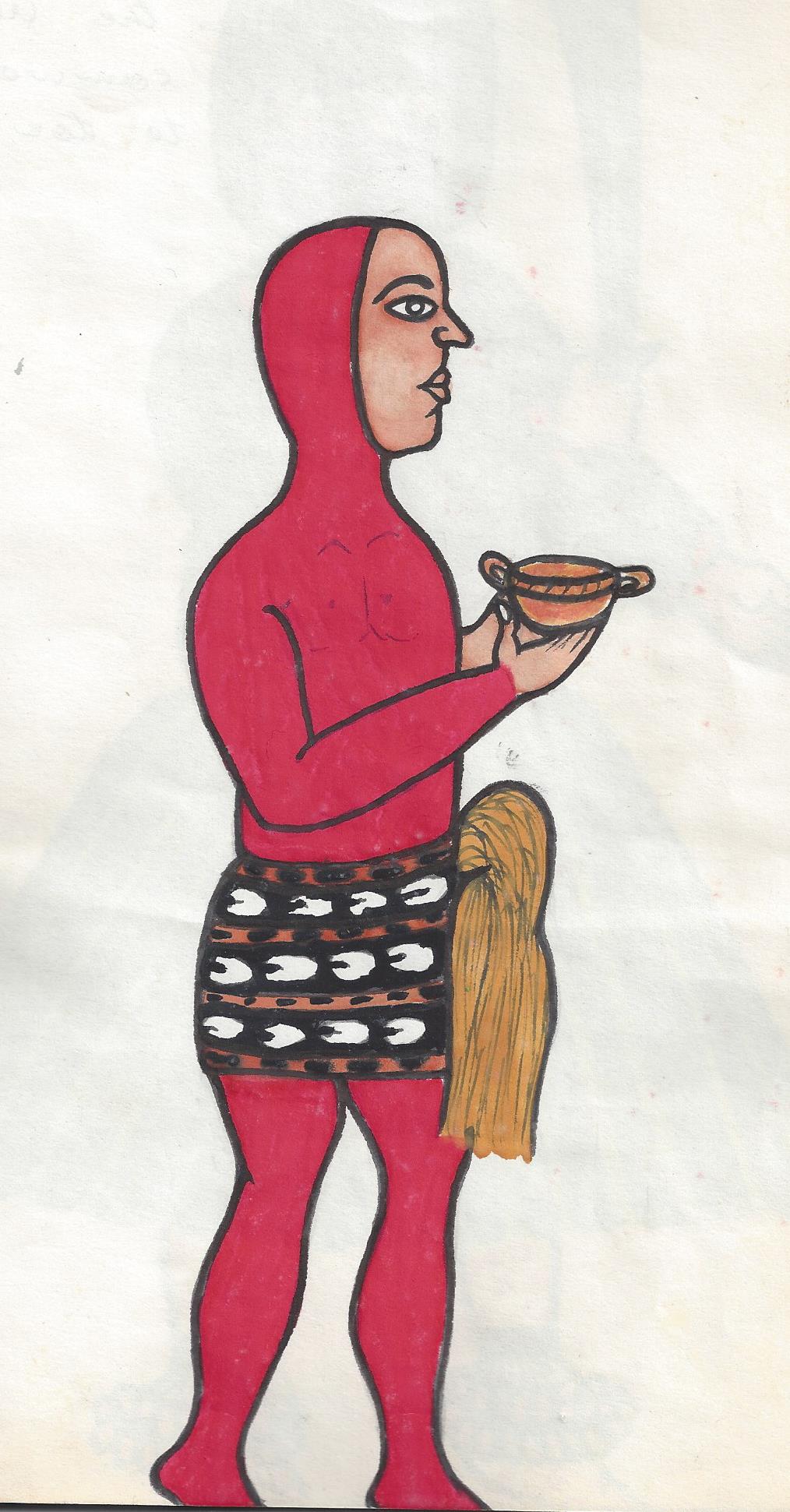

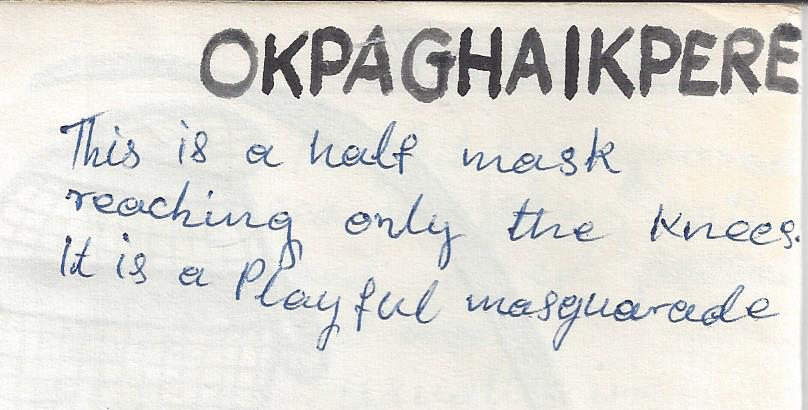

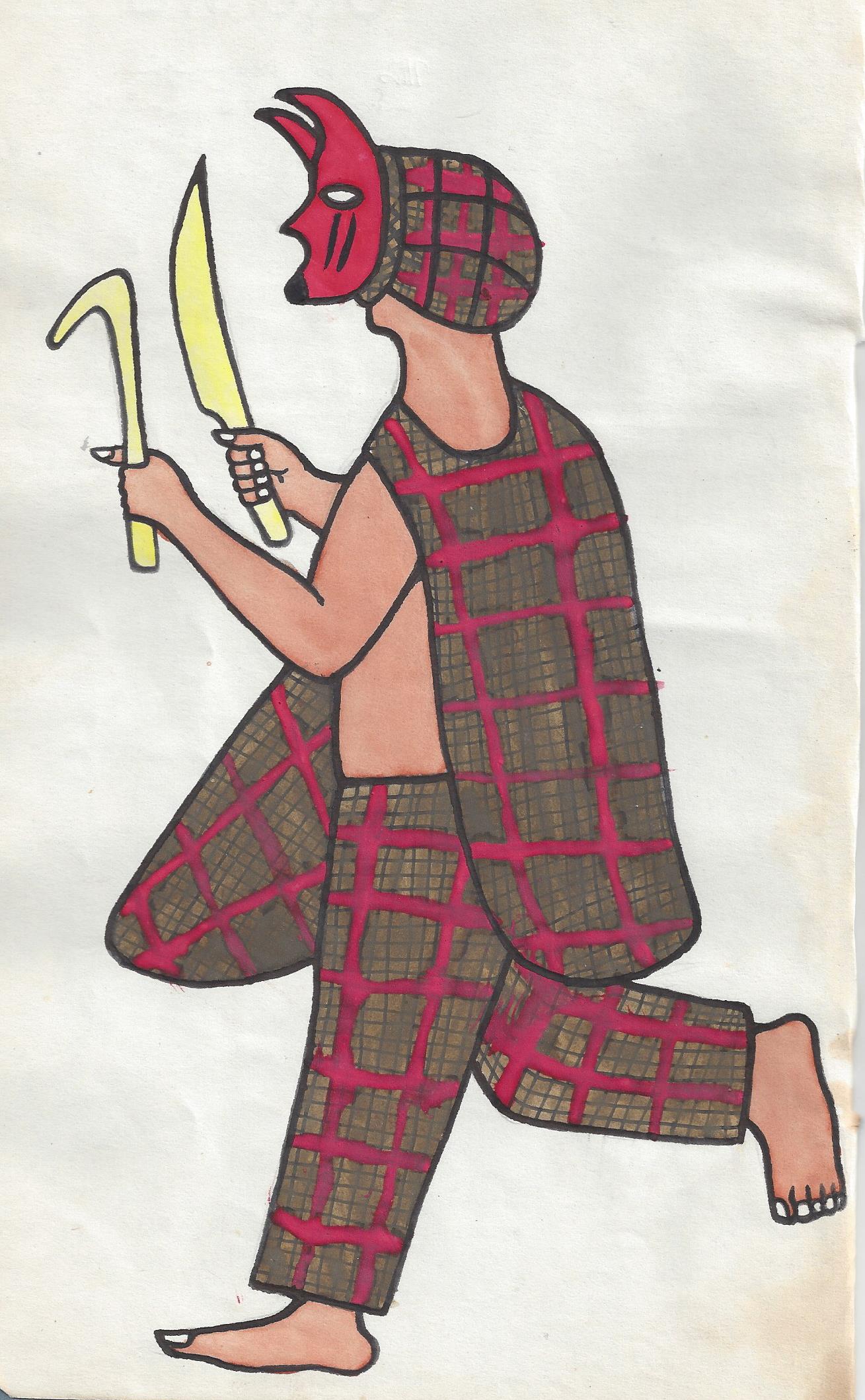

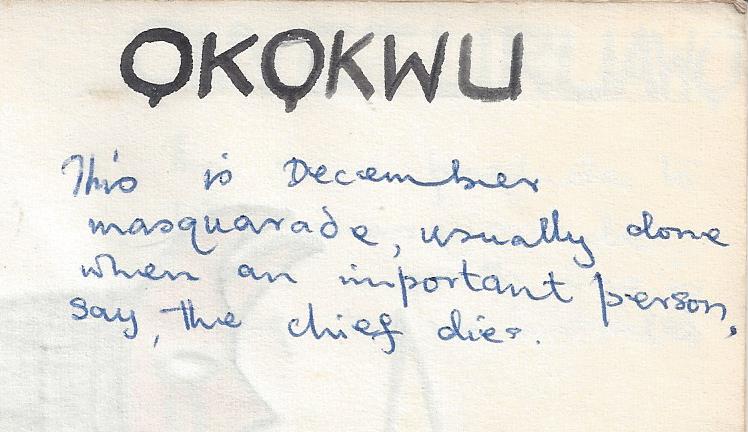

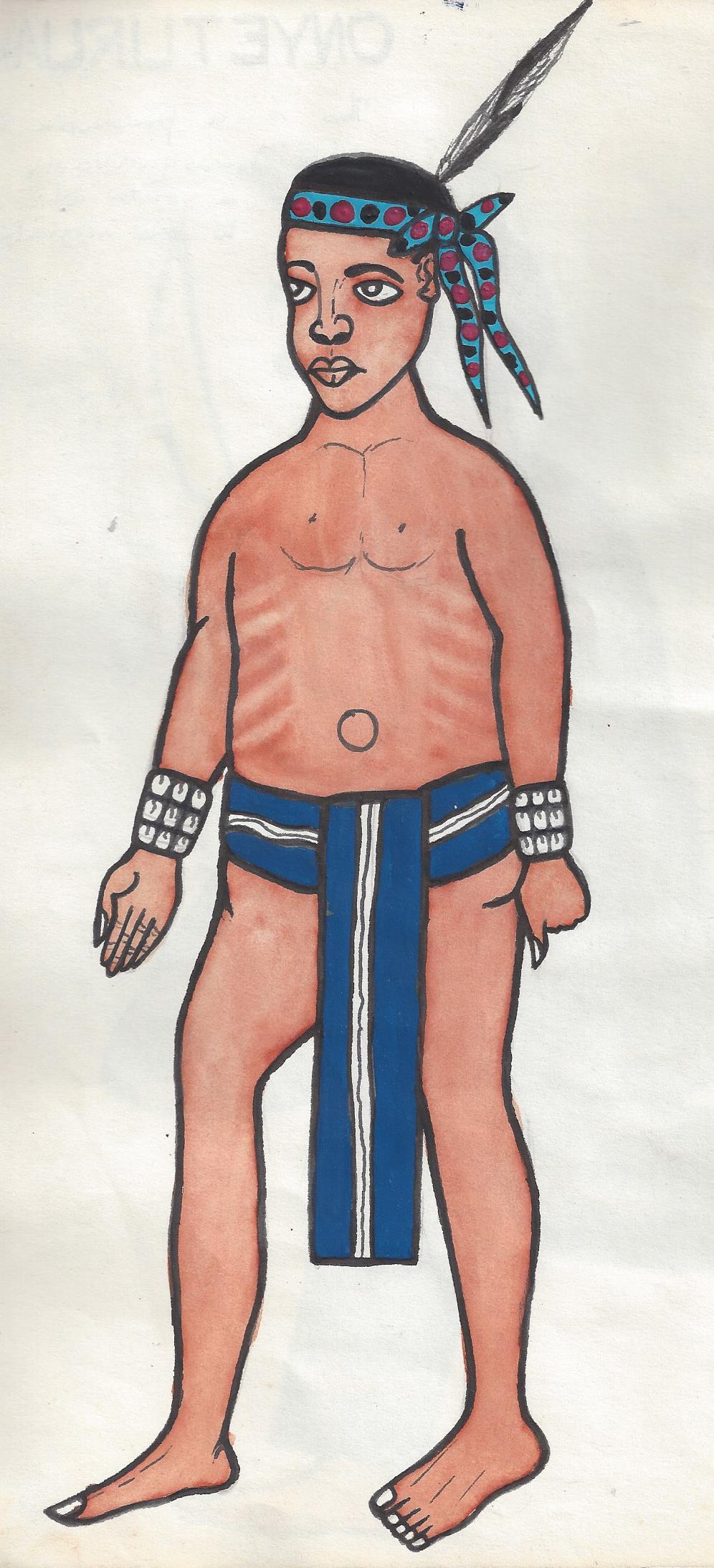

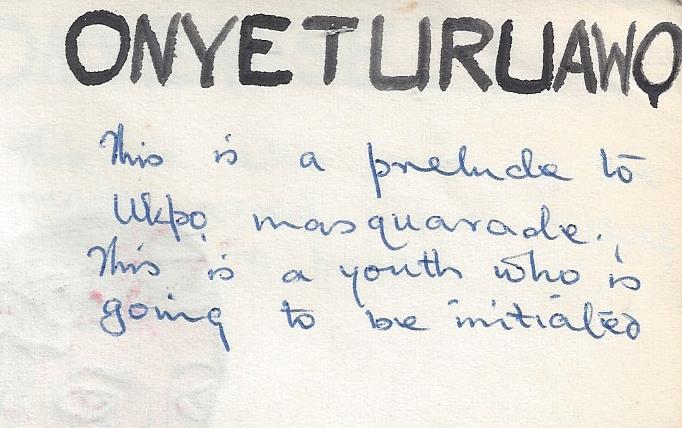

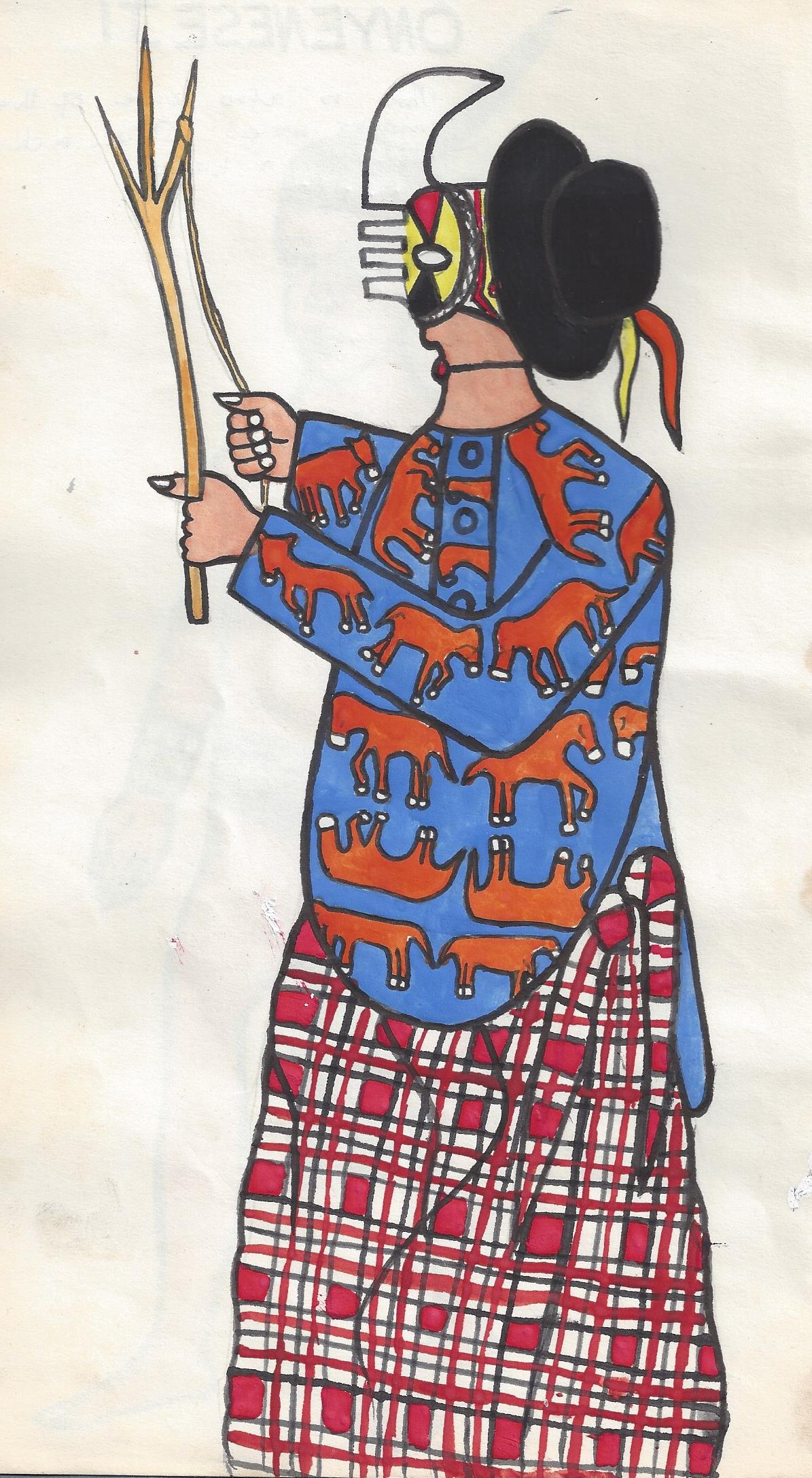

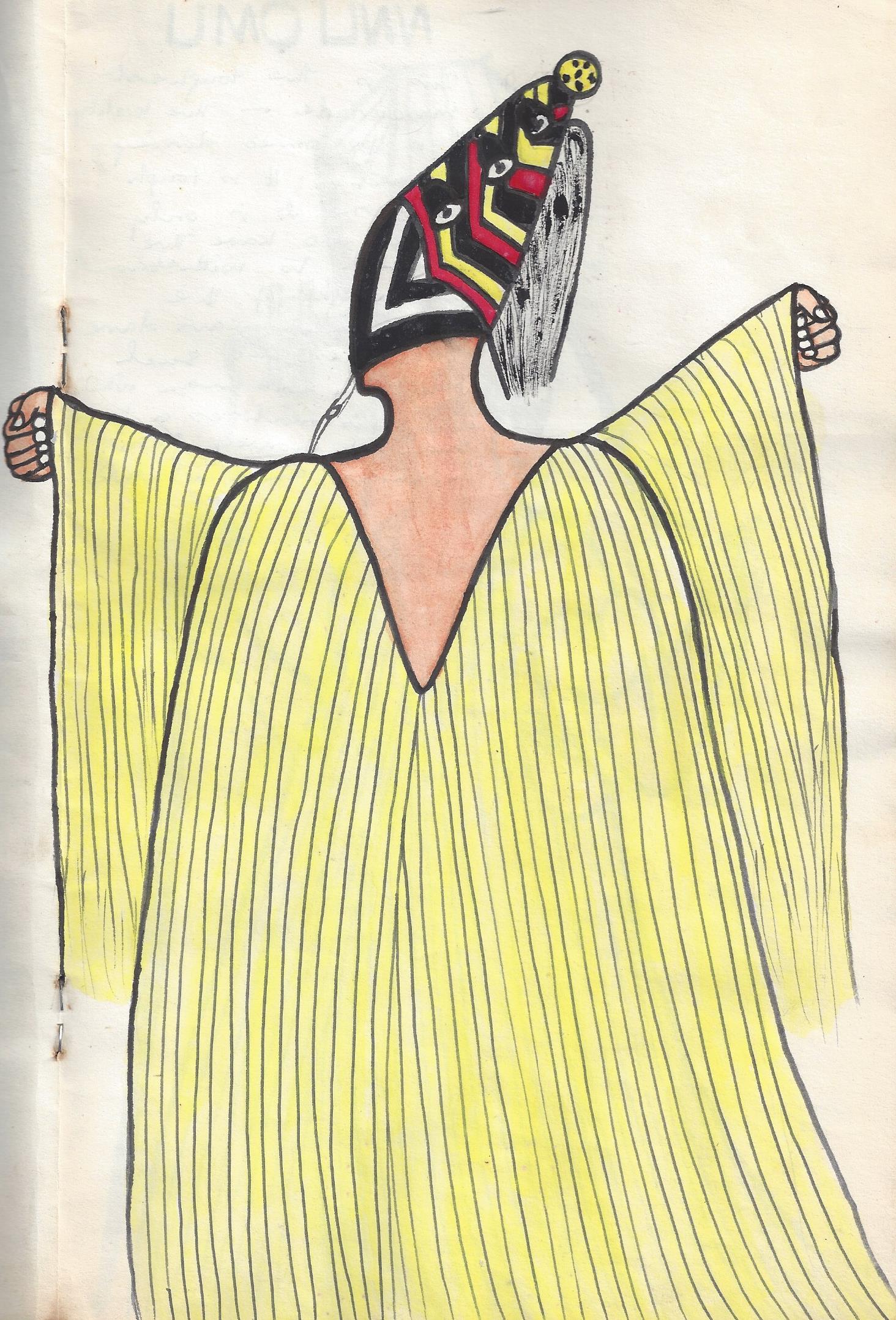

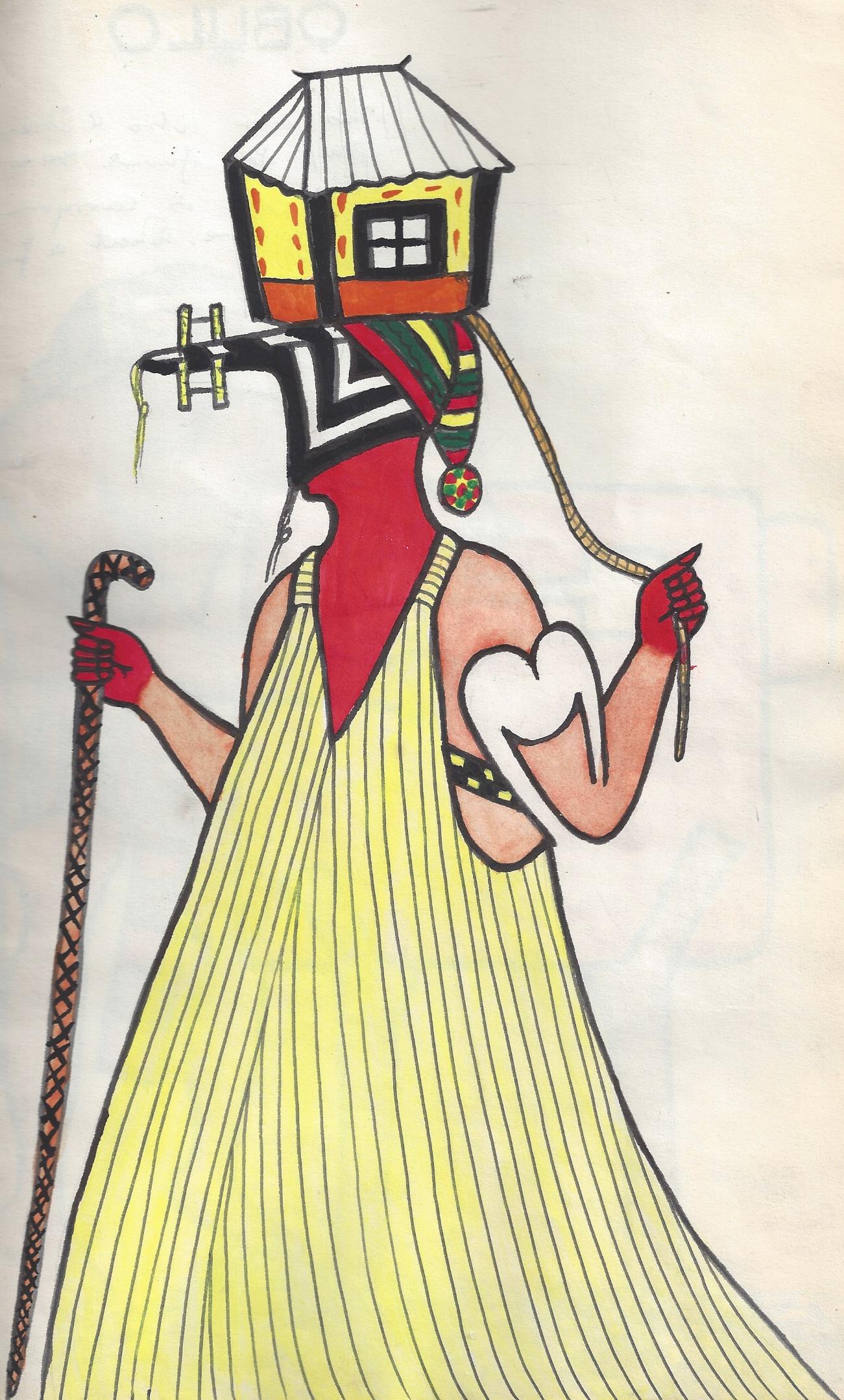

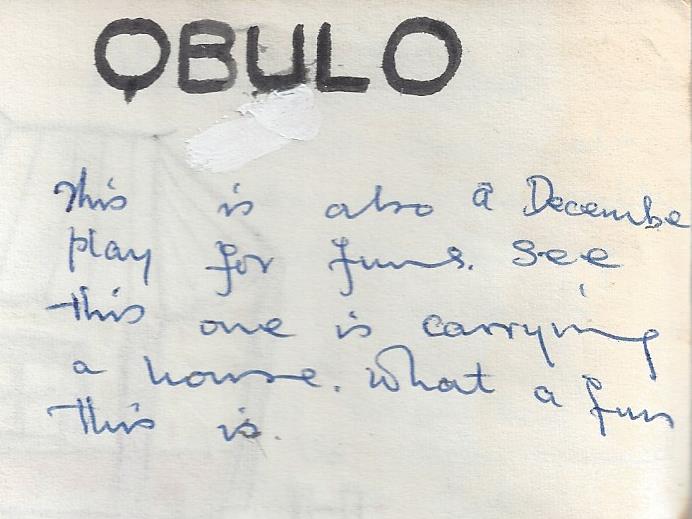

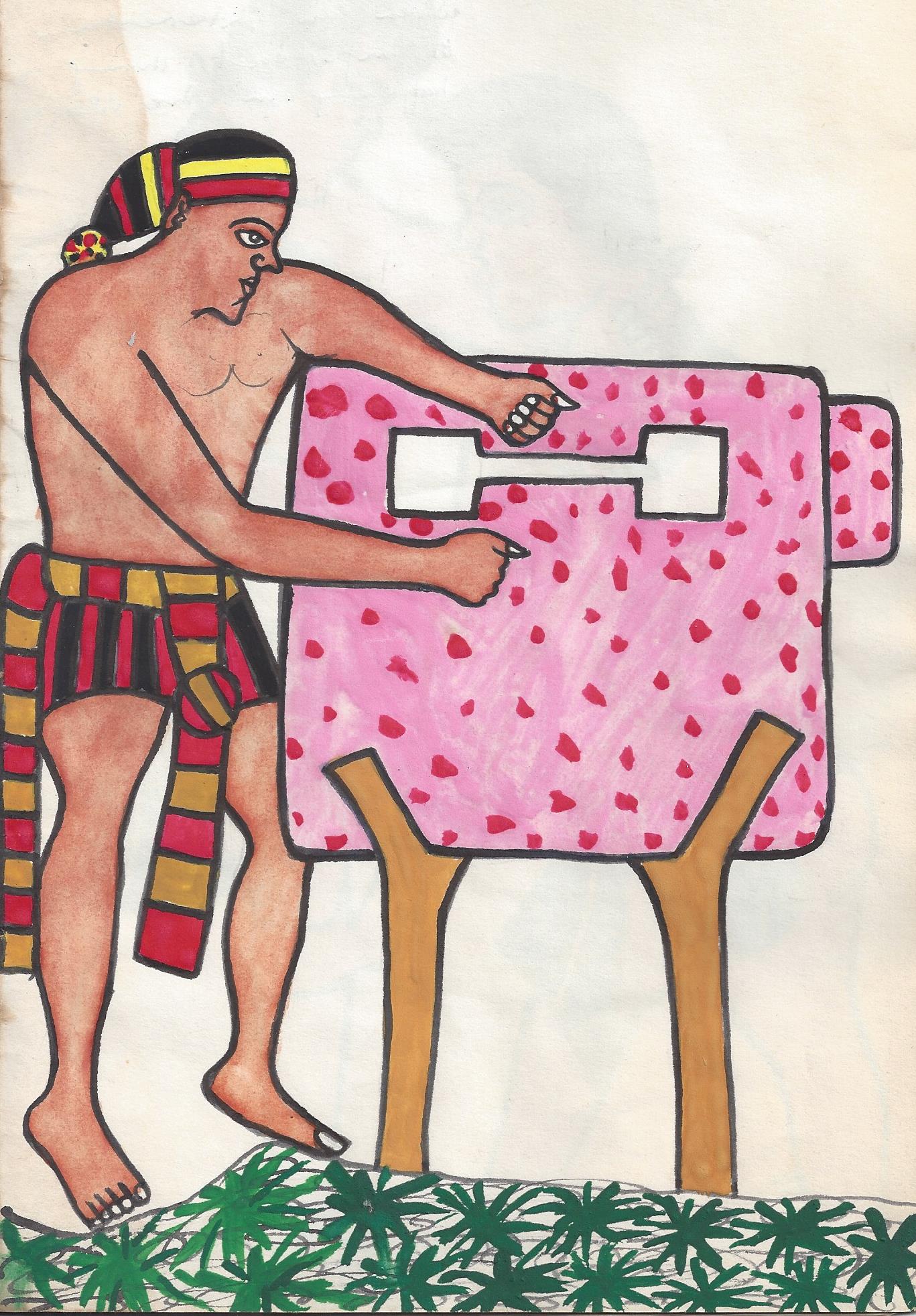

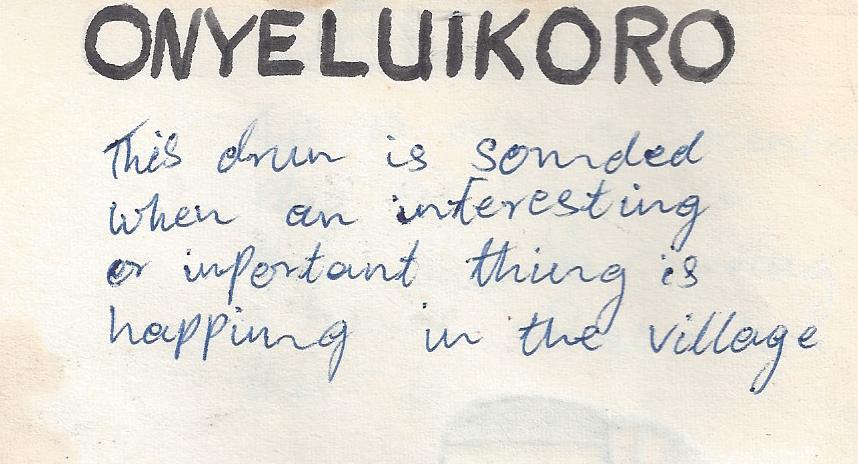

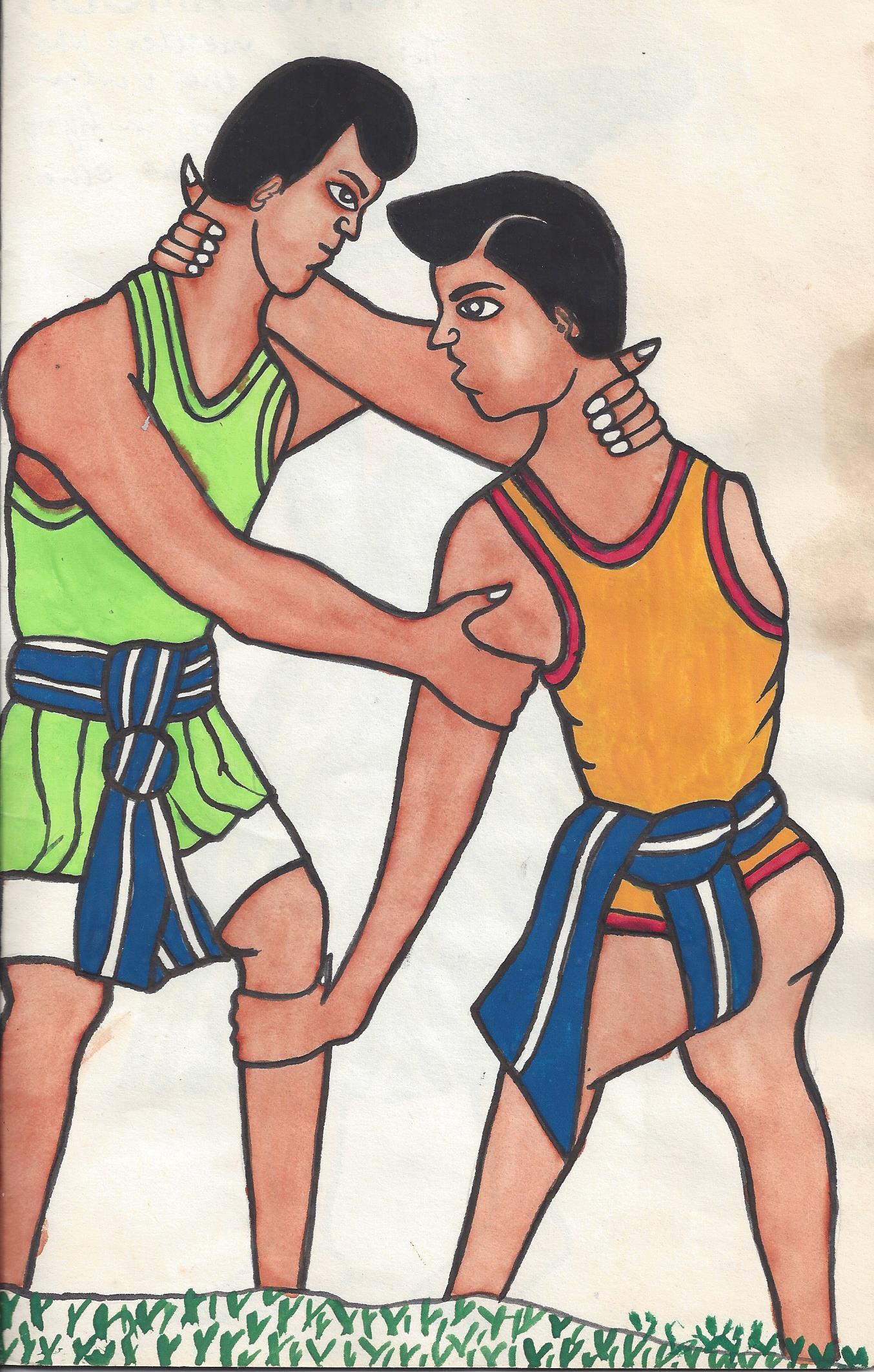

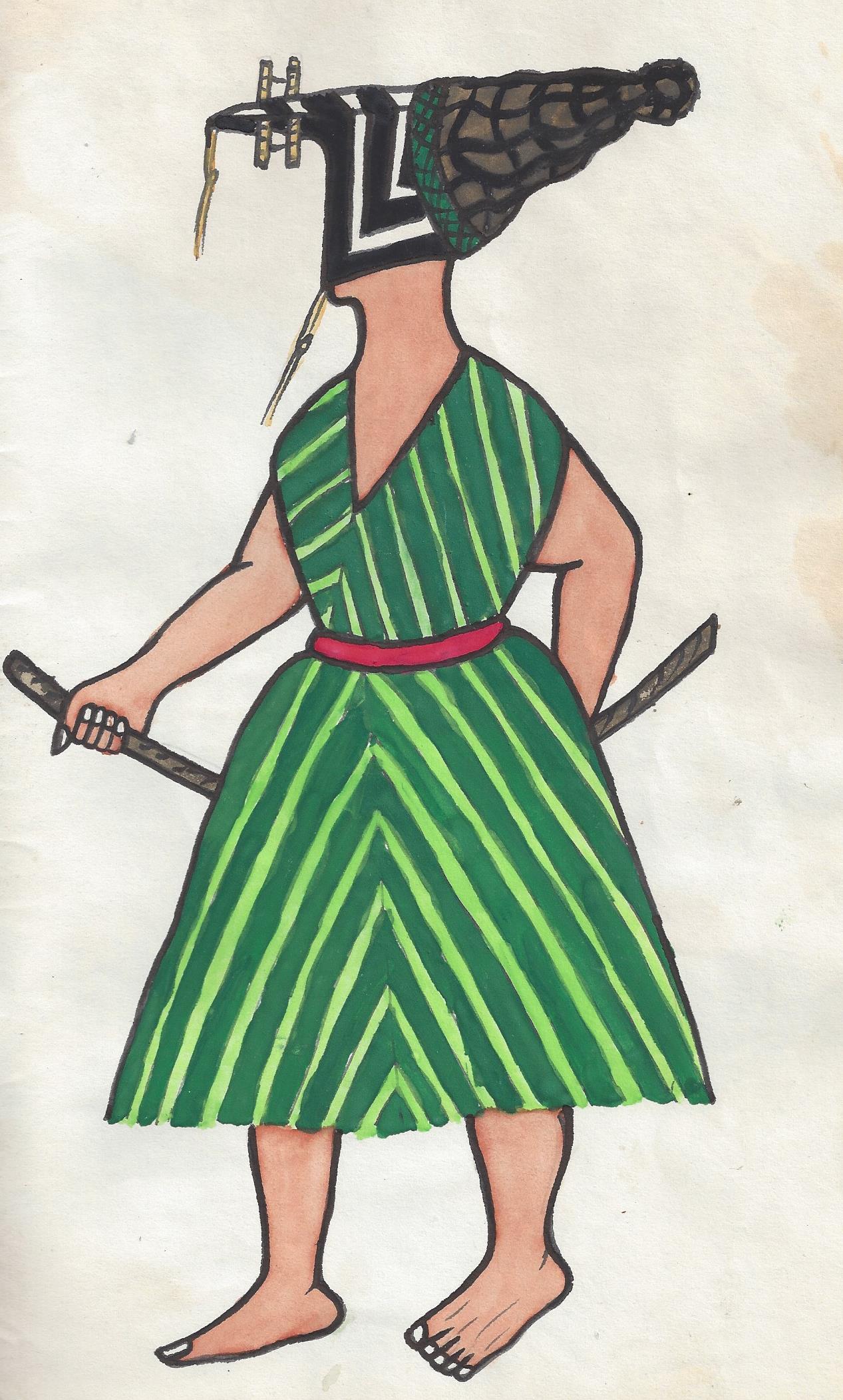

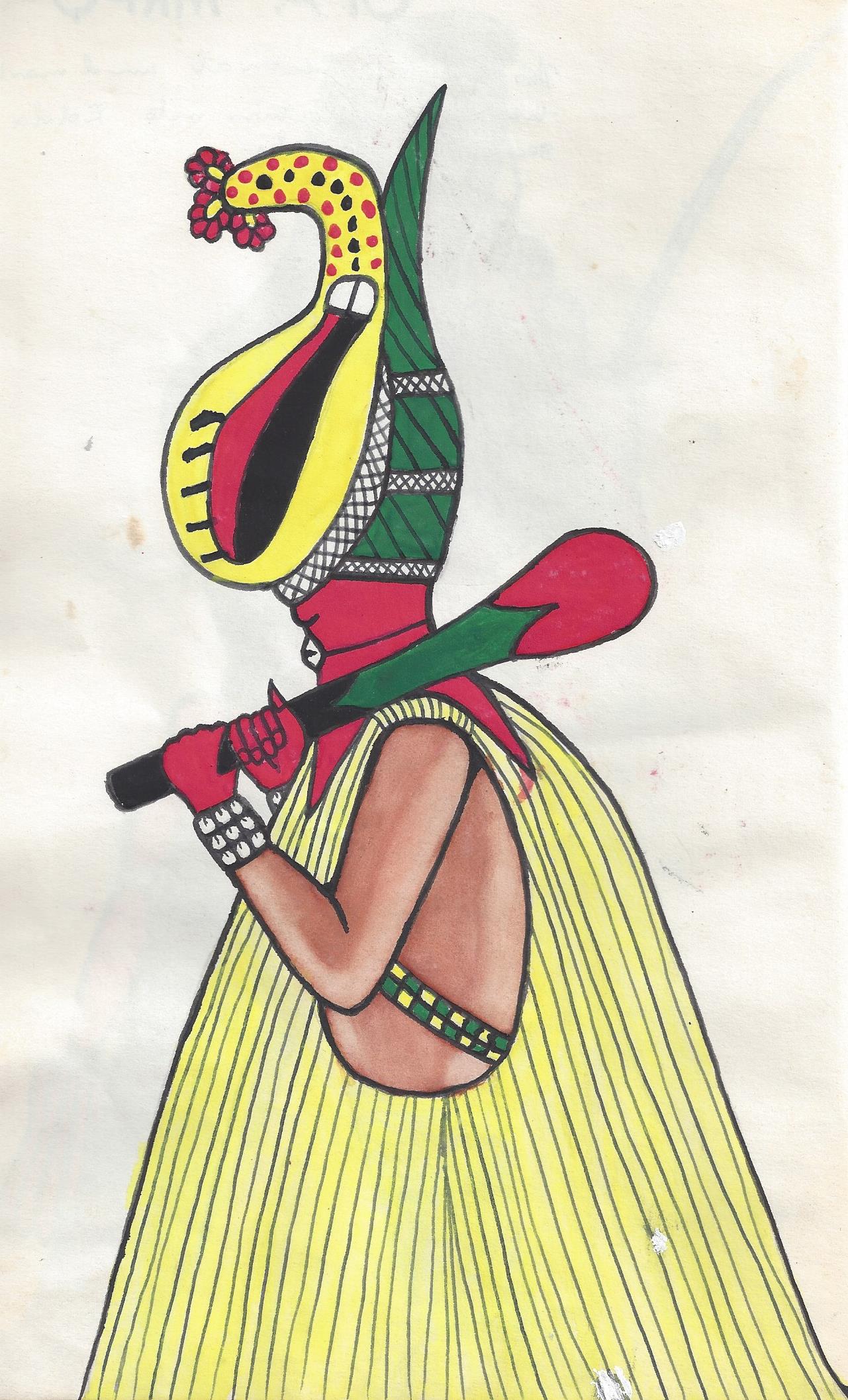

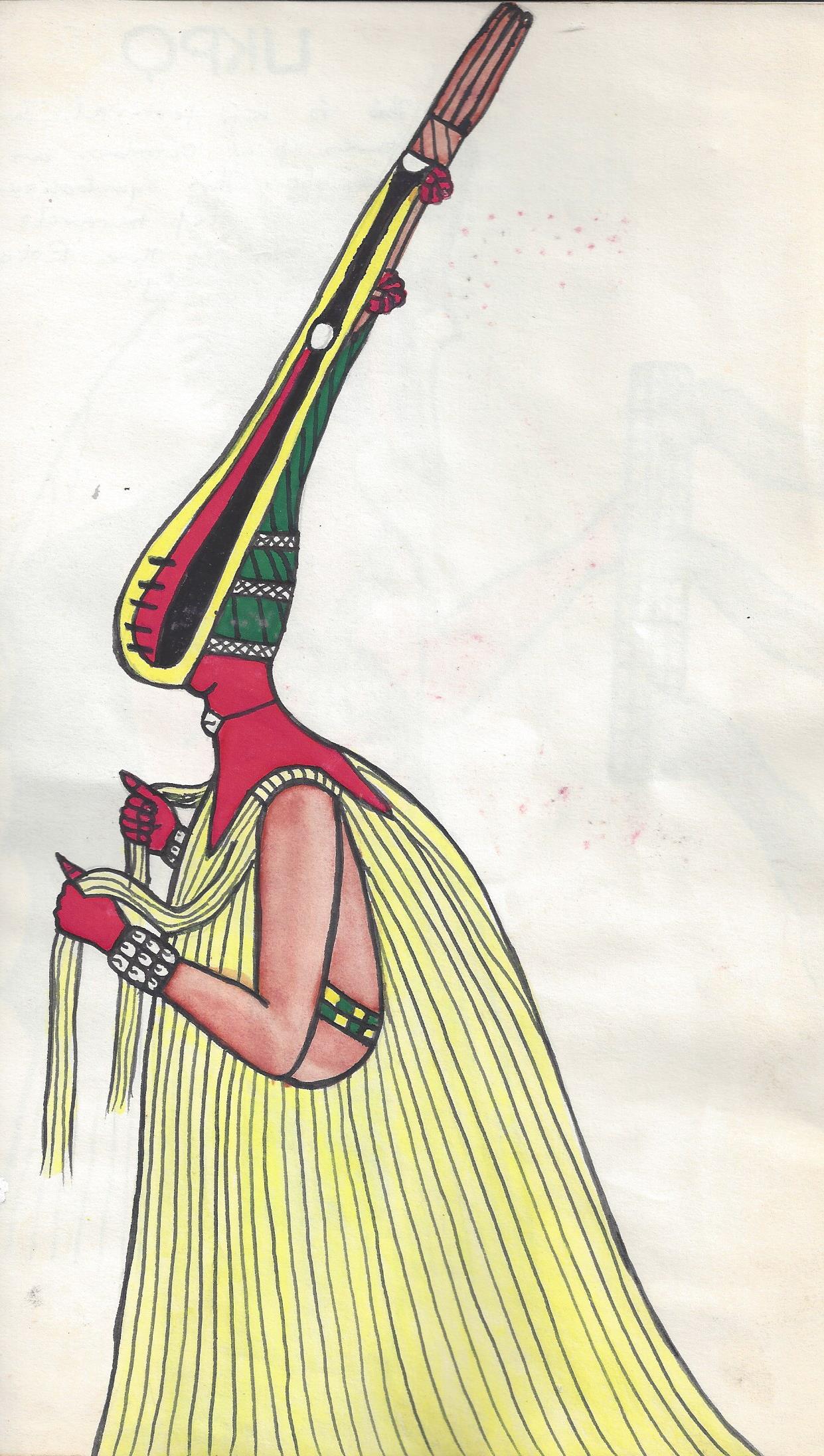

If I wasn’t around to see masquerades and couldn’t take pictures of them anyway, an idea and opportunity suddenly presented itself. Why not hire this teenager to produce watercolor paintings of so many of these masquerades? Fidelis acknowledged that he had detailed knowledge of the masquerades in his home village of Edda, just outside Afikpo town. I had collected a few Edda masks earlier and they can be found in the Gallery. Here was an opportunity to see what the accompanying costumes looked like, and to document the appropriate celebration or festival as well.

What he produced for me was thirty paintings in color. In 1972 I shared these with Prof. Robert Thompson of Yale’s African Studies Department. These made him more excited than I had ever seen him. I believe I showed them to University of Michigan Professor of African Art Ray Silverman about 2010 when he came to view the collection at my home in Bay City, Michigan. No one else had seen them since 1966, but in 2023, I took them with me to meet with two old Peace Corps friends in Boston. They were Donald Cosentino, Professor of African Art Emeritus, UCLA, for decades previously the editor of the fabulous African Arts journal. Joining us was Phil Peek, recently retired as Prof. at Drew University, New Jersey, also a scholar in African Arts, and a specialist in Lower Niger Bronzes., who had been stationed with the Isoko people in the Niger Delta.

Don, Phil, and I all met one another at the Nigeria Peace Corps Training Program of Summer 1964, held at Columbia Teachers College, NYC. At that same program was Henry Drewal, who became Prof. of African Art at the University of Wisconsin/Madison.

Henry wrote the most spectacular publication ever on the History of Yoruba Art, which is listed in my Bibliography. Together, the three of them helped establish the academic study of African Art as a serious subject in American universities.

At Don’s condo in downtown Boston, I pulled out the watercolors by Fidelus Orji Arua.

Together, we turned the pages one by one, and they were delighted. They encouraged me to do something more with them, so, as a beginning, I am sharing them on this website, Chapter Four. For 59 years, these paintings have been unseen otherwise, stored with my masks and statues in Bay City, Michigan.

These paintings were made on the pages of three schoolboy copybooks. They measure 7” x 11”. There are ten pages per copybook. Altogether, there are 30 paintings. As part of its history, I scanned the front and back covers of the copybooks, which came from Port Harcourt.

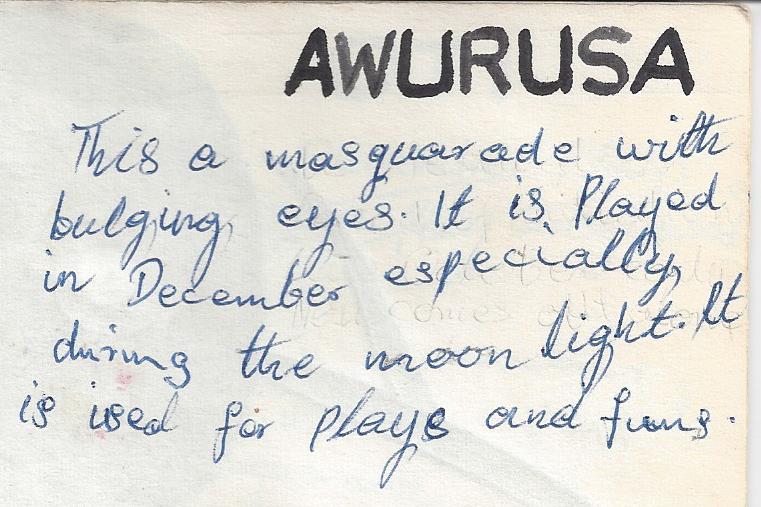

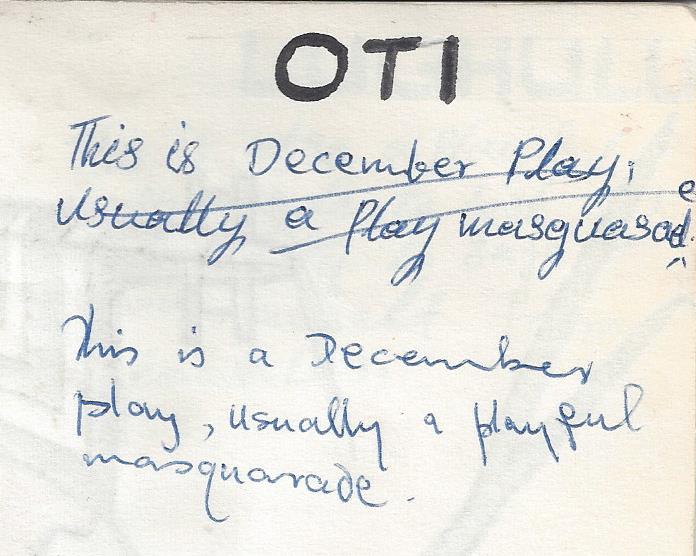

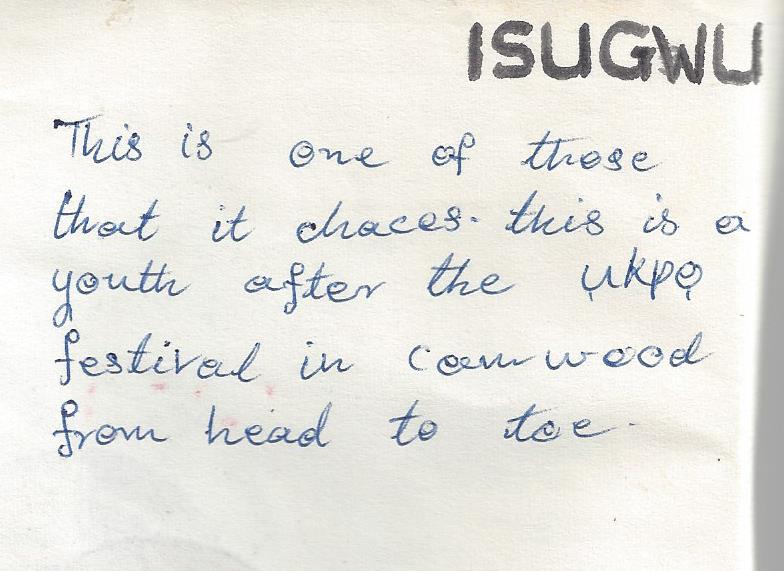

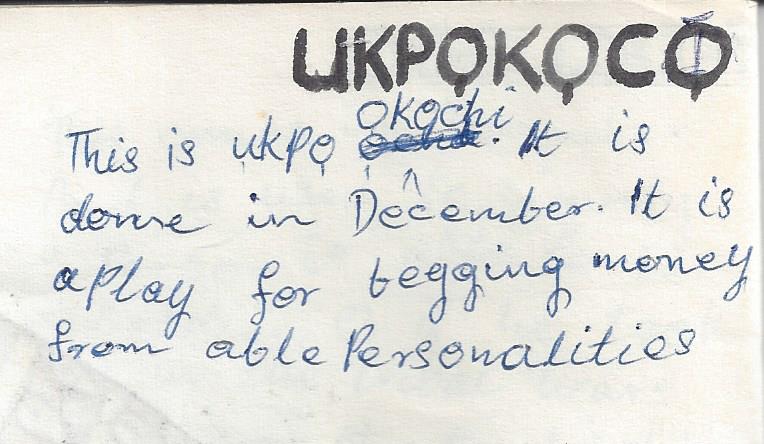

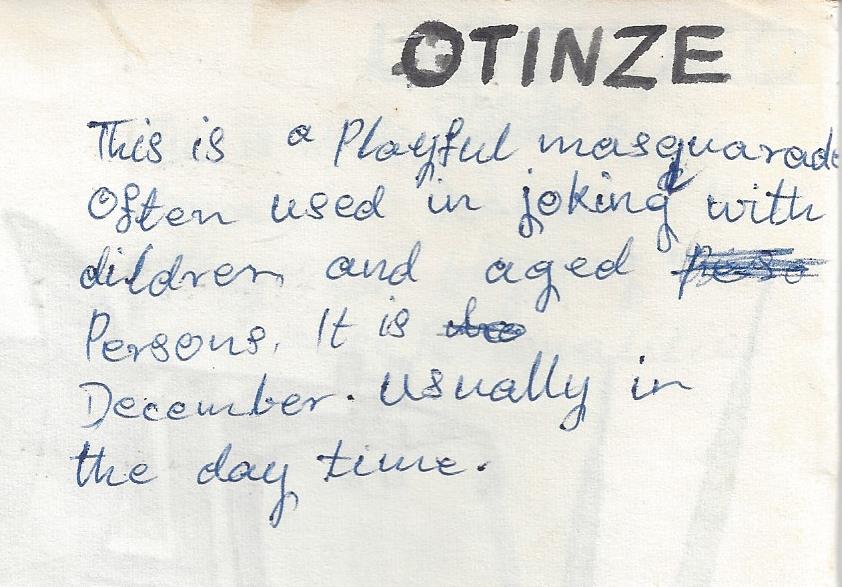

I requested that the artist place his identifying information on the upper backside of the painting. This was done so that if they were ever cut out of the copybooks for matting and framing (a major project of its own), the provenance would remain with the painting.

The identifying information is presented in the artist's handwriting. It is expressed in his charming language. I found his craftsmanship and attention to detail to be amazing. He carefully reproduced the prints found on market cloth, precisely traced arching parallel lines on raffia skirts, and nicely captured the details of the masks. To me, his workmanship is exceptional.

My wife Julia is a talented commercial artist. She has considerable experience with watercolors. Recently, upon examining these paintings more closely, she noticed that the colors were uniform and opaque, not variable and blotchy, so typical of watercolors. She speculates that Fidelis was using gouache. Gouache is an opaque paint, also water-based, but made up of a higher pigment load than standard watercolor paints, plus a binding agent.

I never asked Fidelis about this, assuming, perhaps erroneously, that he was working exclusively in watercolors. It would be a mystery to me how gouache paints found their way to Afikpo in 1966, but maybe they were available through the school supply vendors where he purchased the copybooks. It is a mystery.

I am happy to present the masquerade paintings of Fidelis Orji Arua of Edda village, Afikpo Region, Abakaliki District (in 1966), Eastern Nigeria. I hope you are as charmed by these paintings as I am. You can increase the size of each image by clicking on it for closer examination.