Masks

Igbo Masks

The Igbos still had a vigorous masking tradition in 1964-66. It was stronger in some areas than others, such as the rural villages, depending upon the forcefulness of the local missionaries.

There is a lot of background material that is important to understand regarding masking among the Igbo. For more elaborate information, download and read portions of the text I prepared in 1968 for the Exhibition for the collection at the University of Michigan Museum of Art. This is available above through the Home Page, yellow cover. Please see the brief paragraphs on Secret Men’s Societies, Festivals and Celebrations, and Igbo Masquerades.

Igbo masking traditions vary—what is common and traditional in one section of Igboland is not necessarily found in another. The masks of the Afikpo region, far on the eastern extreme of Igboland, are highly developed, but I found none of their mask types used in the northern, central, or southern Igbo regions. Likewise, I did not find the masking traditions of maiden spirit and animal spirit masks, so strong and widely spread elsewhere, to be present at Afikpo.

Afikpo Masks

I collected a great number of masks in Afikpo and the closely related villages around there: Okpoha, Edda, Amaseri, etc. Peace Corps Volunteer Jack Williamson was stationed in Afikpo and had become friends with the brilliant anthropologist Simon Ottenberg from the University of Washington. Ottenberg did a lot of research and published many important books on masking there. Through them, I was able to meet the main carvers, which led to my meeting many other carvers as well.

In the Gallery Section above, the Afikpo Region is covered from Pages 1-7.

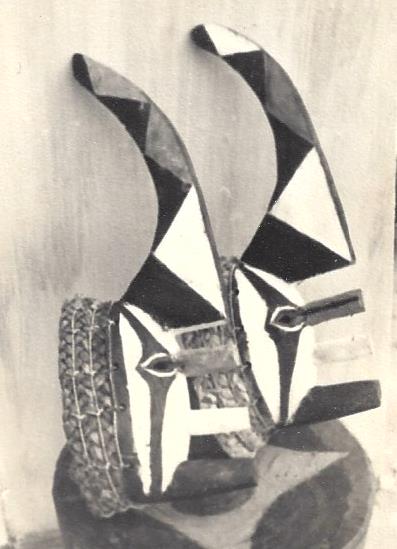

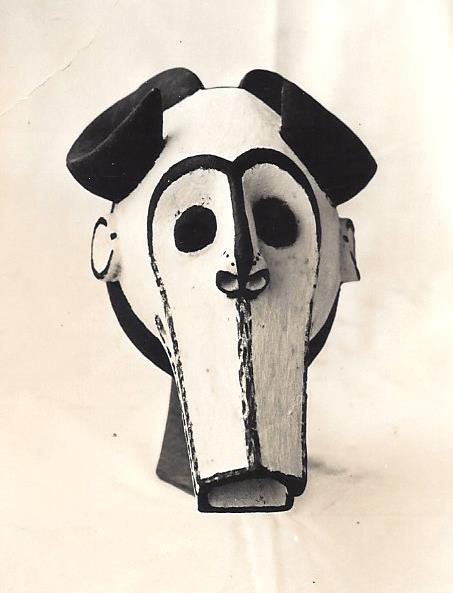

Yam Knife Masks

One of the most impressive mask types from there is the mmaji the yam knife mask, i.e. the machete. In Afikpo, the blade is quite literally tall, erect, slightly curved, and decorated with large colored triangles. However, in Amaseri the blade is swept back further and downwards a bit. In Okpoha the machete blade is rendered in such a circle-back that the tip nearly touches the base. In a few cases, the blade is no longer free-standing but is actually connected to the base, making an enclosed circle.

We may never know how or why this design feature evolved and diverged over the decades. I just wanted to point out what I observed. I also noticed that the designs placed on the blades varied from carver to carver. The same carver may switch up his patterns from one mask to the next, yet they all qualified to be mmaji masks in the eyes of the audience.

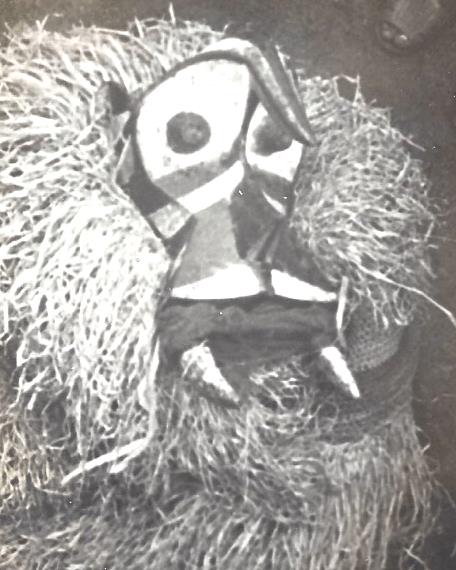

The Gallery shows this type on Page 1, Item 102; Page 2, Item 119; Page 4, Items 149, 141, 145; Page 5, Items 153, 154, 155; Page 6, Items 156, 157, 158, 159. Below is a photo taken by PCV Jack Williamson of a masquerade at Amaseri. Of all of the pictures I have seen of Igbo masquerades to me, this one is the most intense.

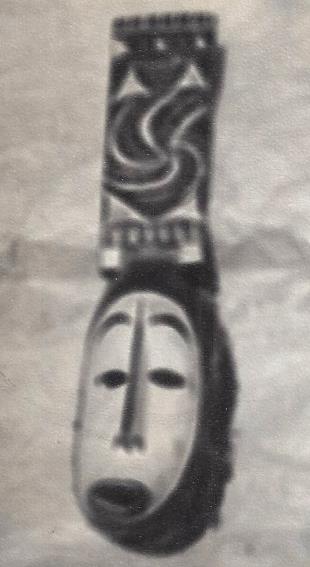

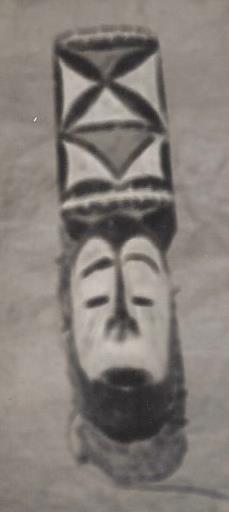

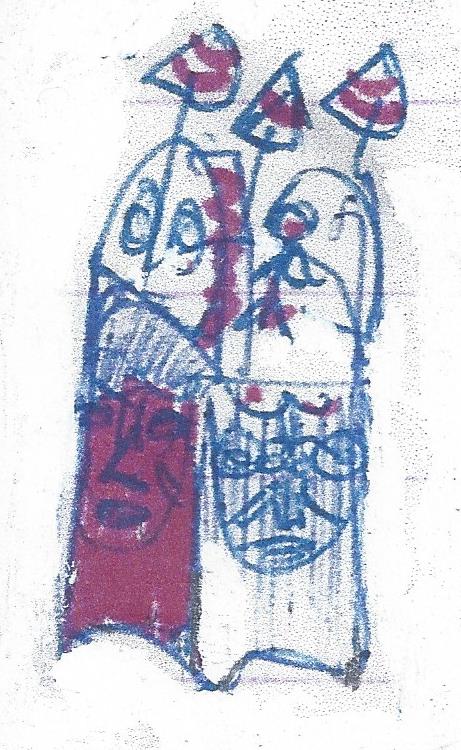

Mba Masks

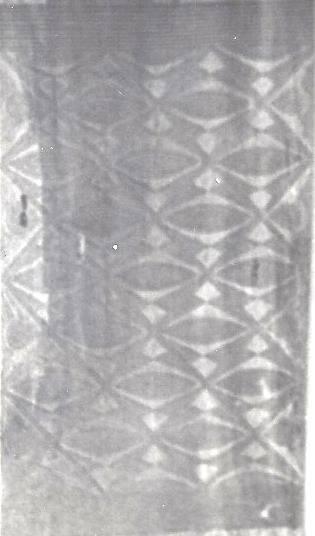

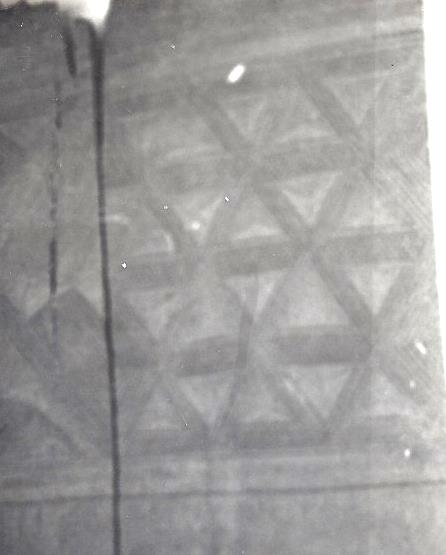

The mba mask can be identified by the tall, rectangular panel presented above the face. This type was found in all of the villages of the Afikpo region. Notice the great variation of design patterns. A given carver did not necessarily use the same pattern on every one of his mba masks. He often changed them, always with a tasteful geometric design. Some carvers used interlocking triangles. Others used more curved shapes to fill the area. I often wondered if these patterns had names related to a phrase, a saying, or a proverb. If so, any of those could, in turn, carry a bigger meaning, such as a message of wisdom or a warning.

Refer to the Gallery for any detailed documentation I collected for this type. See Page 1, Items 107, 108, 109; Page 3, Items 129, 130, 131; Page 5, Item 150; Page 6, Item 169.

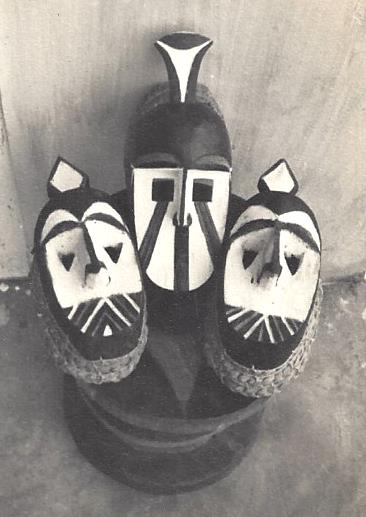

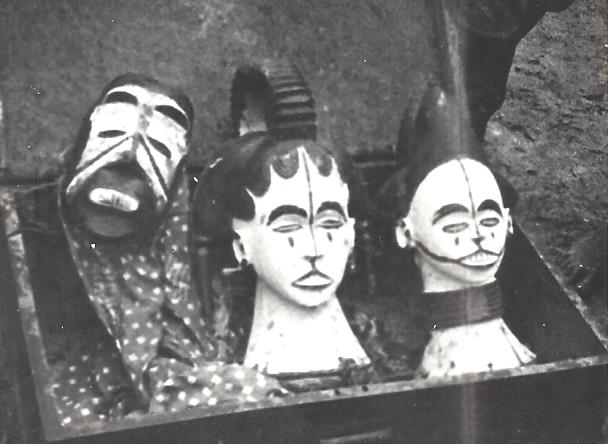

This group photo displays the wonderful variation of Mba designs. The group of three masks is all by the crippled carver in Afikpo, named Nnale Ejo. Many more examples of his excellent work are pictured in the Gallery.

This amazing series of mba masks were found at the men’s lodge in Afikpo where they were stored. It is very unusual that custodians would allow them to be photographed. These are used masks, many needing refreshing for their next use. That usually involved some touchup paint work. Being used in traditional ceremonies they qualified as antiquities, protected by law, not to be removed from Nigeria.

Note: If I wanted a given mask for myself, I would have the carver make a new one for me, for payment of course. Any new one, NOT having been used in a traditional ceremony, but being as genuine and authentic as the former, did NOT qualify under the protection of the Antiquities Law, and COULD BE sent out of Nigeria. I double checked with the National Museum in Lagos more than once, and their typical response was, ”Could you get a copy for us at the Museum?” and I often did. But, they said, “If you can get your hands on an old one, used, no longer in service, we would especially like that as well.” So, we were able to help them out on several occasions.

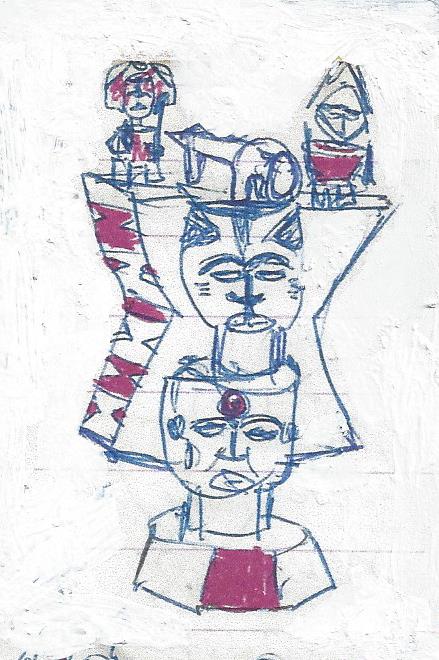

Opanwa Masks

The name of these interesting masks translates to “She is carrying a child.” In this case the child is carried on the head of the mask (as opposed to being wrapped onto the torso of the mother). I never once saw a baby being carried on a mother’s head. Some of these can be found in the Gallery with their documentation. See Page 1, Items 103, 104, 106; Page 2, Items 122, 124; Page 3, Item 125; Page 4, Item 146; Page 6, Item 168. One is also pictured in the Exhibition Catalog, #38. The masks below were photographed in the men’s lodge, the first needing freshening up for its next performance.

Okonkpo Masks

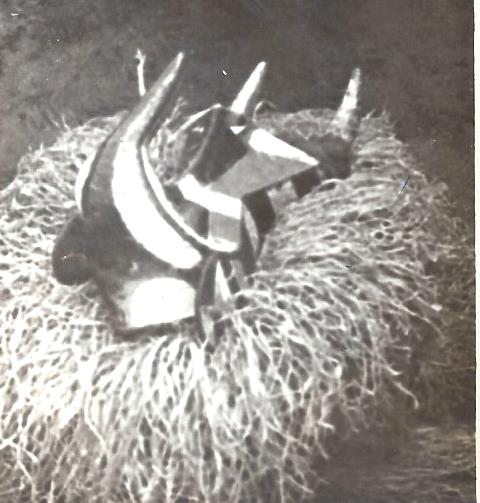

Okonkpo masks are very prominent in Afikpo masquerades. Once again, note the various patterns seen above the face with raffia fringes. To learn more about their role and use, see the Exhibition Catalog #13, and the Documentation portions of those displayed in the Gallery above. See Page 2, Items 120, 121: Page 3, Items 133, 134; Page 4, Item 146; Page 6, Items 166, 167.

The first mask is by Chuku Okoro, the major carver in Afikpo. The second is by Nnale Ejo, another prolific carver. The third is by yet another carver. The group of three is a picture taken at the men’s lodge, being masks in use. The lighter colored version comes from a village neighboring Afikpo, which uses a different coloring tradition. The final photo compares the designs from several carvers.

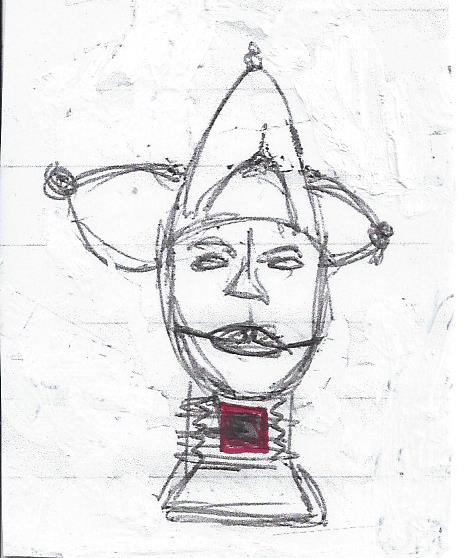

Bekee: White Man’s Mask

During the British Colonial period (1900-1960), colonial administrators, missionaries, and explorers slowly became part of the Afikpo world. At some point in the distant past, a carver created a mask for white people. The story goes, the reason they are referred to as Bekee is that an early missionary in the area was named Bakie, and an Igbo approximation of his name became the name for all white people (although while I was there, that was universally replaced by onye-ocha, or one who is white.) See Ottenberg for more details.

I did notice that some of these masks had a hair part carved into and painted on them. This most certainly mimicked the white man’s parted hair style, so new and different to the Igbo of the day. I have seen pictures of other masquerades also using this mask, but without the hair part. I did learn that these masks were used by the drummers in Afikpo and Okpoha, where they represented spirits. In those cases the costume would not be conventional British dress, but rather flowing fabric, or the raffia (I call it haystack style). I never saw any such white man’s mask outside of Afikpo. More pictures are available in the Exhibition catalog #50. In the Gallery, see page 1, Item 101; page 2, Items 116, 117, 118, 123; page 7, Item 179. The following pictures are field photos of Afikpo masks; however, the last one on the right shows three from Okpoha, of a different style, resting on a slit gong.

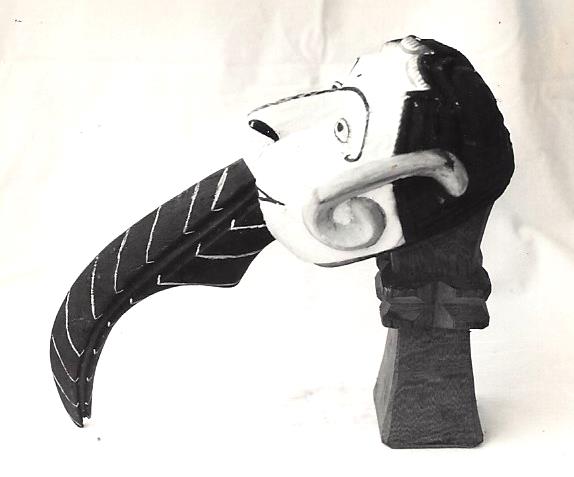

Woodpecker Masks

The Afikpo name for this character is Otogho kpo-kpo. The kpo-kpo is their way of describing the popping noise this bird makes when it is drilling into a tree. These are smaller masks and oval in shape. They are characterized by protrusions representing the two parts of the beak of the bird. In some versions, the beak nearly sticks straight out. In others the beak is rendered as curved and tapered, nearly meeting at the tip. Pictured here are a few photographed at my apartment in Enugu. The single photo is one carved by the master carver of Afikpo, Chuku Okoro, a friend of Simon Ottenberg. More can be seen in the Gallery: page 1, Item 105; page 3, Items 132, 135,136; page 4, Items 137, 147; page 7, Items 176, 177 from Okpoha in a totally different style, employing a face mask plus a small bird figure perched on a arching pair of carved legs; page 8, Item 186, another version from Okpoha using a face mask plus wire legs supporting a carved bird.

Chuku Okoro was a master carver, whose work was always finished in very precise detail. He was friendly, outgoing, and anxious to please. This led to a larger carving workload for him than normal. He told me there was a time period when carving was taboo in Afikpo, which he said he had violated and had gotten fined for! Thereafter we and others had to wait a bit before we could receive the masks we had ordered from him.

Here are field photos of three masks I was able to bring out and are pictured in color in the Gallery.

Children's Masks

These masks for children in Afikpo are named Achali. I believe they are used under the guidance and control of the Secret Men’s Society. Ottenberg’s work on Afikpo has greater information on this. The first picture shows a host of Achali I was able to collect, photographed in Enugu. Note that themask on the far right has a head upon it, and is NOT an Achali, but is called an Mba mask. As usual, the carver exercises a great freedom in using a variety of designs and colors on the masks, but the audience all understand they are Achali.

In the Gallery above you can find examples an Page 4, Items #138, #139, by the carver Nnale Ejo, and #144 by carver Chuku Okoro.

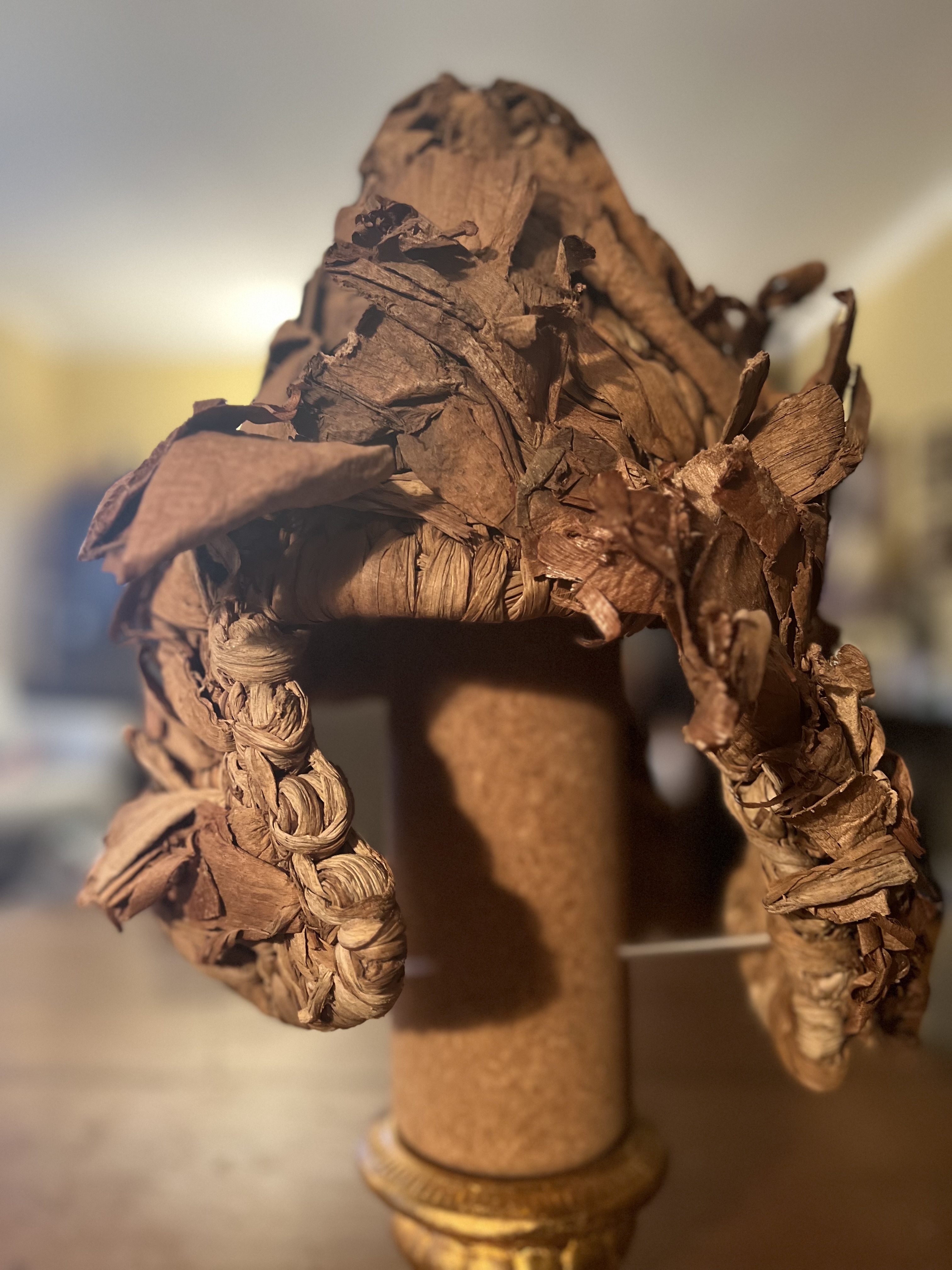

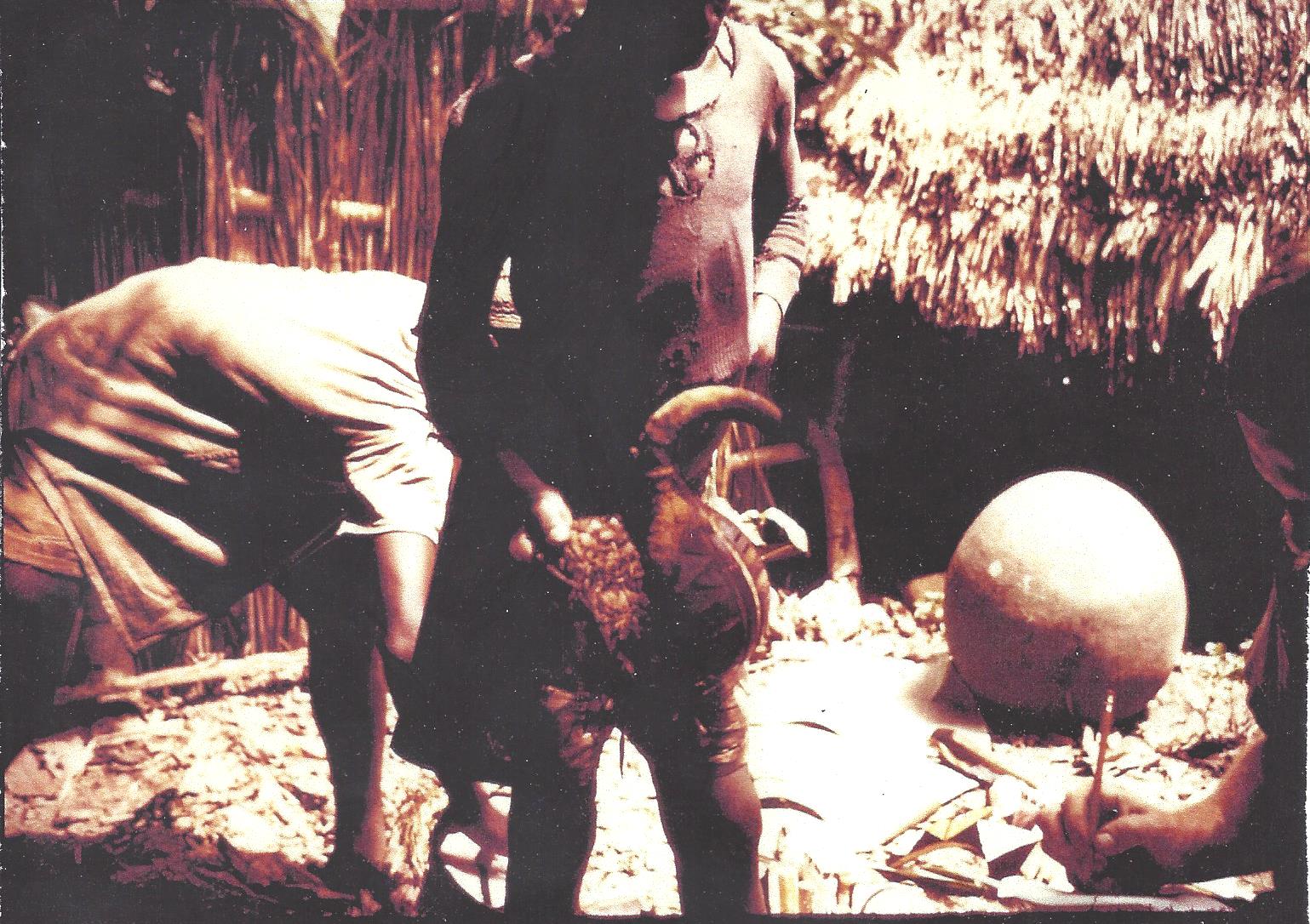

There is a mask that is very fragile and never makes it out of Nigeria, because it perishes so rapidly. It is made from a gourd, and it is attached to a collar of soft fiber such as raffia or cocoyam leaf. Here is a photo of this rare mask taken in the Men’s Lodge in Afikpo, where the masks are stored between performances.

Starkweather collecting data on masks in the Afikpo Men's Secret Society Lodge, 1965.

Other Igbo Masks

In other regions of Igboland, I found traditional masquerades to be as equally prominent as they were in Afikpo, There were many different types of masks, used for a great variety of social purposes. Some troops came out at specific holidays, such as harvest festivals and Christmas! Others came out as needed to convey messages that certain things were not quite right in the village. It might be as simple as somebody getting too big for their britches, who needed to be watched carefully, or even taken down a peg. Another group of masquerades might appear to warn the public of some serious matter or some growing crisis.

Masquerades were also related to the traditional burial process. When a person died, the Igbo knew the spirit left their body, but they traditionally believed that the spirit did not ascend to the spirit world immediately. It hung around for a while. It needed a ceremony to complete the transition of the spirit away from the human level. This was the so-called “second burial.”

At such a time, the family would have to put on a feast for the public, which could be expensive. It usually took a bit of time to accumulate the wealth necessary for such a crucial event. If it took too long, the spirit of the deceased, still hanging around, could get injured or could start to create trouble. Masquerades would be part of that “second burial” event, and it is here where the well-known maiden spirit masks are central.

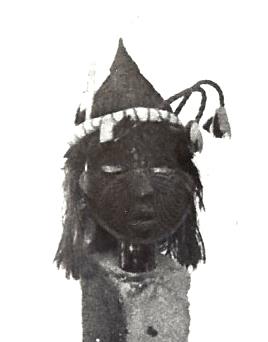

The hair styles of Igbo women in 1965 were much simpler than those in historic times. Long, long ago the women would wear elaborate, built-up hair-dos, assisted with maybe palm oil, clay, ribbons, etc. Usually these employed high crests, and were highly decorated.

The oldest of these masks, found in the major museums in Britain (and elsewhere) display this amazing crested hair. It is rendered with meticulous care on masks by master carvers of deceased generations. In terms of the challenge for careful execution by carvers, these Igbo headdresses rank with the highest level of carvings I have ever seen in the pictured literature of West Africa. I find them to be right up there with the antelope headdresses executed by the master carvers of the Bambara.

The maiden spirit masks are found all over Igboland (except Afikpo). They feature white faces (the Igbo masquerade color of a certain class of spirits), with fine features. Arching triangles are commonly found descending from under the eyes, and sometimes above them as well. There is often a pair of dots in front of the ears, and sometimes scarification patterns on the forehead. As is typical in many Igbo carvings, the carver can display a wide range of variations, yet the audience has no trouble distinguishing which masquerade character is before them.

Here are examples of the maiden-spirit masks from an older generation, shown to demonstrate the elaborate hair crest and facial details.

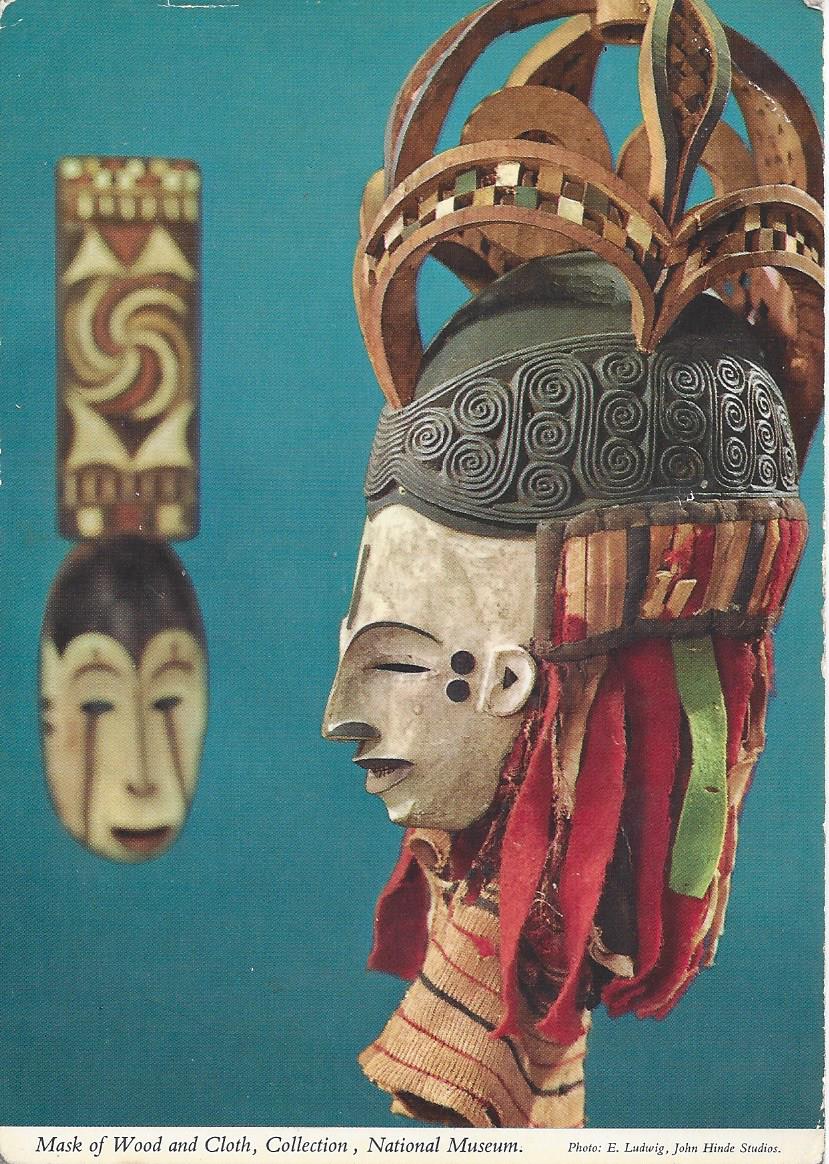

This old postcard from the Nigerian National Museum, Lagos, shows an excellent example. The ribbons and cloth attached indicate the bright colors of the typical costume (rarely collected anywhere). This I would classify as a 3/4 helmet type, as it covers the face and the top of the head, but not the back of the head. By the way, the mask on the left is easy to identify. It is from Afikpo. By examining the style and shape of the face, I can tell it is not by the master Chuku Okoro, whose work can be seen in my Gallery. This one was probably done by one of his predecessors. The very elaborate patterns on the rectangle top indicate an mba type.

The second two pictures show maiden spirit masks photographed (if memory serves) in the Detroit Art Institute in 1971. Masks of this vintage typically show knicks and scuff marks from previous usage. The colored picture shows a mask that almost certainly has been painted by a restorer, or a merchant.

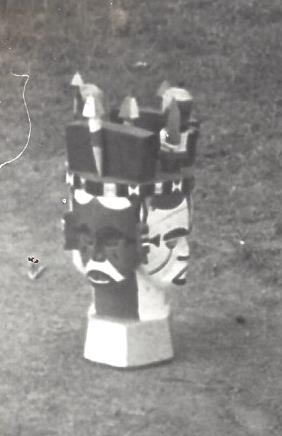

The following mask comes from Udi. It was photographed by Emmanual Duru at Zaria, Northern Nigeria, at a museum display. There was a considerable Igbo community living in Zaria, and (in 1964-66) they had maintained much of their traditional culture there. This mask shows the wonderful built up hair crest and the common dots at the ears, and shapes under each eye. This is an example of remarkable delicate carving by the maker. The back of the photograph is labeled “mother masquerade”, suggesting that this type can depict either a maiden or a mature female. The picture on the right was taken by Afi Ekong of a mask named Okonga from the Awka Male-Society. It is unusual because it was carved with three tiers, supporting human figures and a goat! First of all, the mask is a very ambitious carving. Secondly, despite the impressive structure, the carving is a bit on the crude side compared to, say, the Udi mask above. This mask would require a very strong man to balance it on his head, and still manage to go through gliding and dancing motions. I never saw one of these in a masquerade. It was very rare.

The two maiden spirit masks shown below were purchased from the stall in the Onitsha Market. I have no information on the carver, or the village of origin. Note that the hair crest is present, but not as tall as seen in the other photographs. These never made it out of Nigeria.

Odo of Imilike-Enu

Nsukka is a town north of Enugu, home of the University of Nigeria founded by Michigan State University, which trained Peace Corps/Nigeria Group No.1. All of those Peace Corps Volunteers were sent to Nsukka as college instructors. I happened to be attending the MSU African Studies Center at the time, doing -graduate work, primarily on Nigeria. I was able to sit in a substantial number of their training sessions, and got to know many of them well. I crossed paths with some of these PCVs much later, after I completed my own tour of duty and was working at Nigerian Training Programs in Atlanta and Boston. One was Roger Landrum from Reed City, Michigan (located west of my home town of Saginaw, Michigan). Roger went on to become the Desk Officer for Peace Corps Nigeria, before obtaining a PhD from Harvard. My PC classmate Donald Cosentino assumed that position then.

I learned of a dynamic carver living in a village, Imilike-Enu, north of Nsukka. The carver’s name was Odo. Most carvers did not put any signature on their work, but Odo was bold about it. In the Gallery, on page 10, Item 222 you can see the hair-crest version of the agbogho mask I was able to obtain from him. the Photo section shows the side view, his prowess in carving the hair, and his name prominently painted on it in bright yellow enamel.

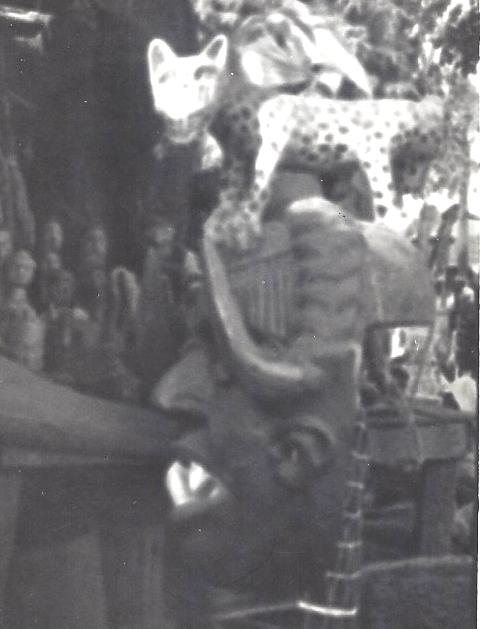

Above is the picture of another of Odo’s masks which he made for me, with a wonderful pair of leopards (and his name painted on it), which never came out of Nigeria. While I was in his studio, I quickly took a number of pictures (apologies for the poor quality) of several figures there. Upon request by a village society (and substantial payment), he would carve a multi-tiered mask and include several of these figures. They would become quite tall and very heavy. He himself would don this great weight and dance it for the masquerade. He was a vigorous and athletic man, to be sure.

The following pictures show many of the figures awaiting assembly on any one of his mask constructions. The first shows a very Caucasian face with a colonial hat. Note that the forehead and nose are decorated with markings which may be seen on other spirit masks. The single figure pictured appears to have ivory bracelets, holding one arm up with an open hand as if something would be placed there during final assembly.

Two figures appear in another picture. Is the one on the right playing an accordion? Another picture of three figures shows one apparently playing a long penny whistle, or a flute, standing next to the center figure with crossed military belts.

In another picture there is a leopard proudly holding down a fish it has caught! Next to it are pictures of two different, but very similar masks. They are very aggressive and are large enough to be worn entirely over the head. I wish I would have been able to get the whole story about their name, role, and purpose.

Here are two shots of a black mask with aggressive teeth shown, and a leopard above the horns. This is obviously not a maiden spirit mask. This could be one of the family of black masks found throughout Igboland for scaring people, a masquerade not to be toyed with. This mask was made in Ikot Ekpene, a village of the Ibibio people, neighboring SE Igboland. It was photographed in the Onitsha market on Emejulu St. Many Ikot Ekpene masks have been seen used in Igbo masquerades.

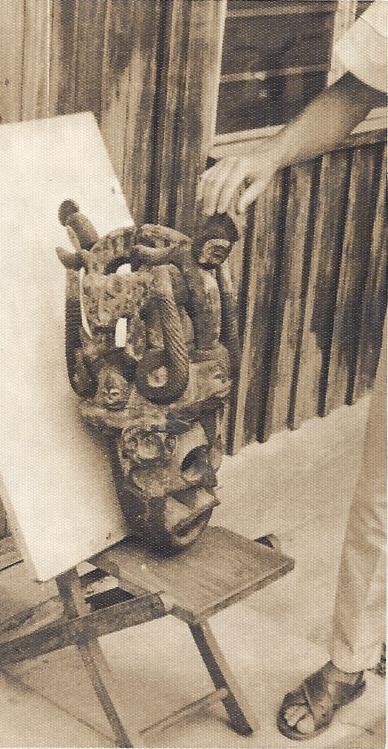

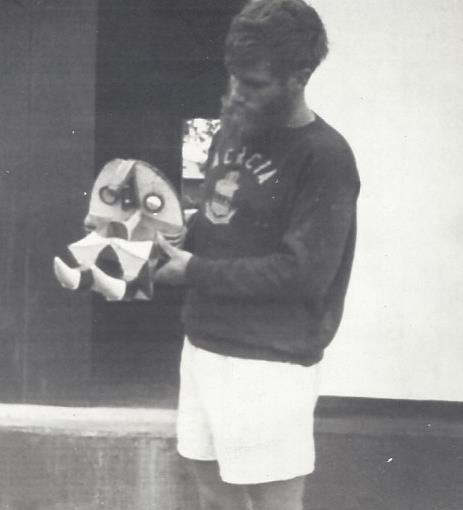

Another style of Igbo spirit masks is found in this complex mask photographed in Ibadan, western Nigeria, at the Ibadan Institute of African Studies. They had no information about its name or village of origin. The hair crest is embellished with animals and snakes. It is being held by Peace Corps Volunteer Joel Vandenberg, who was on assignment as an archaeologist, working with the historic bronzes at Igbo-Ukwu, and the rest. (After the Peace Corps, Joel joined me at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where he earned a Masters Degree in Public Health. We took carving classes together every Tuesday night for a year at Frankenmuth, Michigan from a master German carver. After a few years Joel moved to New Zealand where he lived out his life in the public health field.)

Sammy Onoh

To conclude this section on maiden spirit masks, let me introduce teenager Sammy Onoh. An extensive background story on him will follow, but here I wanted to present this wonderful full-helmet mask he created. Where the previous masks cover the face and the top of the head, this mask also covers the back of the head. It is a rare full-helmet mask. It is hollowed out with great care to accommodate the wearer’s head. I put it on once in Nigeria, but barely got it off, and know better than attempting it again. I learned how proper ventilation breathing space is paramount for the wearer.

The shape of the face is so rounded, balloon-like, it is obvious to me that it is Sammy’s modern interpretation, not a copy, of an antiquity mask, which I would expect to be much leaner. The hair style is not a crest, but a more contemporary style, elaborate none-the-less. Typical marks for this type of mask are located at the ears, and under and over the eyes, but here they are reduced to small stripes. A side view of this mask can be seen in the Gallery on page 10, Item 223.

Another variation of these larger masks can be found in the Gallery on page 8, Item 187. Here Aka Gworo of Inyi has carved a face-covering mask, plus an elaborate hair piece as a separate carving. He has joined the two together with a sewn leather strip, resulting in a conventional ¾ helmet mask. It certainly makes the carving easier. It is also possible that it was difficult to find a piece of wood available that was large enough to render it in all one piece.

In 1965 it was much easier to locate maiden spirit masks carved to cover the face only. The costume maker would then be called upon to create the tall and elaborate hair piece, which would be sewn to the mask. Examples of these smaller face masks can be seen in the Gallery on Page 8, Items 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196. Two of those styles are from two carvers in the same village, Inyi. They are quite different from one another, but carry enough of the markings and symbols to qualify as maiden spirit masks.

These are to be compared to Items 195 and 196 which come from a village not many miles away, in a third style that is quite different from the other two. Cole and Aniakor, in their outstanding book “Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos” produced a map (Map B) showing the geographical distribution of the several and various styles of masking traditions. I learned that if one unique mask was very popular in some other distant village, a member of the Secret Men’s Society would sometimes commission a copy for their own inventory. By that method, these masking types blended and expanded.

Sammy Onoh and His Serveral Masks

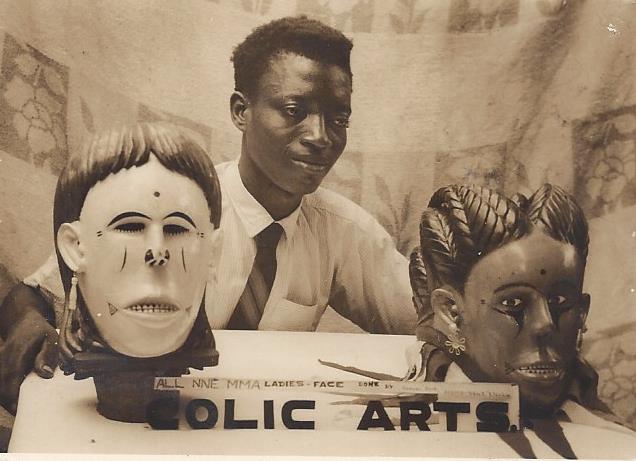

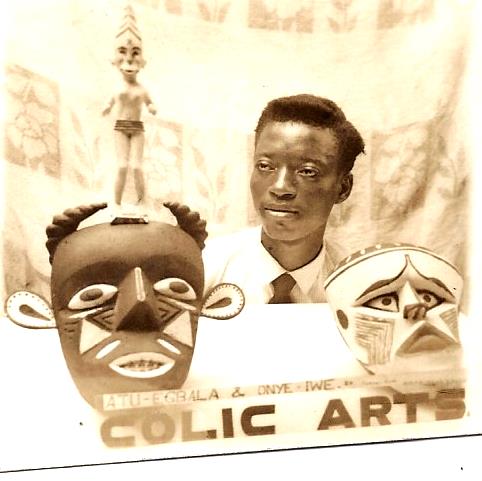

One day I heard about an arts and crafts show being held at the Enugu Market. There I met a teen-age young man who had carved a turtle with a back that lifted off revealing a shallow storage area for coins and pound notes. He had also made a standing white bird with a hinged hatch on the back. This was a place to hide one’s watch and other valuables. He also made a scorpion for snuff or kola. There was also a 2-1/2 foot tall image of a man in European dress, with hair glued on. This young man was talented and had a great imagination. He also produced a pair of facemasks of his own design that looked like nothing else I had come to know in the Igbo style. These are shown below in his portrait photo.

This was Sammy Onoh, who lived outside Enugu to the west near “Nine Mile Corner” in a village named Akama-Ngwo. Here is a picture of the entrance to his house. The second picture is of my Jeep and the always-present cluster of friendly kids who appeared wherever I stopped my car in a village. Sammy named his business “Colic Arts”, because he told me “Once you see the quality of my art, its memory will stick with you like a colic.” How’s that for a business slogan?

We struck up a friendship and I asked if he had ever carved any traditional ceremonial masks from his village. He was a little startled, and said “No”. Soon after I loaned him a retired mask from Inyi, which is pictured in the Exhibition Catalog identified as a field photo following Item 120. He produced a copy for me which is shown below. Note that the paint work significantly changes the appearance of this mask.

The name from Inyi is “onyeama”, the hawk, which is a warning. The expanded story is “egbe anu uze” translating as “the hawk doesn’t hear noise”. It carries the message: “Once the hawk calculates in the sky and starts his dive, it is too late to do anything about it (there is no use for the farmer to shoot at it and try to scare it off. People can shout and yell but it keeps coming)”. I was told it was “for fun” and can come out at any festival. Being able to collect this extra information opens up the likelihood that many of these masquerade characters carry with them a moral, a tale, a concept of some truth. It suggests a whole fresh area for academic research. This original Inyi mask I donated to the National Museum, Lagos in 1966.

After the fine job he did on this piece, I asked if he would be willing to find a local traditional carver and get him to “open the trunk” presumably filled with the historical designs grounded in his village. He did just that, and when I met him again he showed me a piece he had copied. It is “oji onu” shown in the Gallery on Page 10, Item 216. It is propped up by a divination piece in the side view.

The ulaga and oji onu masks combine human and animal features in a horizontal headdress. The carver says this one is used by children for fun in the traditional Ngwo festivals around the Christmas Season. Ulaga and Oji Onu are believed to be borrowed several generations ago from the Ijo (Ijaw) people who occupy the Niger Delta. These masks are known far up river in the Onitsha area and have spread eastwards to Okigwe, and by this example as evidence, northwards to Enugu area as well.

Another old mask that came out of the Ngwo trunk was called “ike ibagwa” , carved by Ugweze Akobuilo of Ama-Ngwo, a man I never met. This antiquity piece was also donated to the National Museum, Lagos. Sammy made a very reasonable copy, painted it close to the original and added some fabric around the edge of the mask, as was traditional. He also entered it in the 1966 Festival of Arts/Enugu, and won “Award of Merit”. This encouraged him to look further into the advantages of carving traditional art.

He went on to make other copies for me of historic masks found “in the trunk”, and his craft improved with each piece. Examples of his work can be seen in the Gallery Page 10, Items 216, 218, 219, 220, 223. I became very proud of the progress he was showing, and his youthful age increased the chances of him carrying on the traditional designs of his village (if he survived the war!).

More Carvings by Aka Gworo of Inyi

Aka Gworo Nwokechesi was the most active carver in Inyi, producing a wonderful variety of masks. A few of them are pictured in the Exhibition Catalog, Items 98, 106, 109, 113, 115, and 119. All of the ones I was able to bring back to America are shown in the Gallery. See Page 8, Items 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 197. Page 9, items 198, 199, 200, 202, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, and one ikenga on Page 12, Item 320.

In reviewing my field notes I uncovered some additional information for some of these. For instance, the dotted mask with long horns and beak (Gallery Page 9, Item 109) is named “mbara uguru aza eruchie” transliteration word for word is: compound, Harmattan Season, if swept, gets covered up again. The fuller meaning is: You don’t really have to bother yourself about sweeping the compound during Harmattan (dry season with winds entering from the Sahara Desert) because it will be littered with leaves again right away. I wondered if the several dots he painted on it were to depict the litter/leaves.

Aka Gworo carved many of these animal spirit masks. In many he carefully placed a small chip of mirror in the eye sockets. When looking at the masquerade, if the sun angle was just right, you got a flash of light from the eyes. The villagers were then convinced that this masquerade was indeed a spirit. I brought a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers to him, as well as other American visitors, and many of them were delighted to purchase one of these splendid masks. You can see copies of the ones I brought home in the Gallery Page 8, Item 197, and Page 9, Items 198, 199, 200.

This is an opportunity to show the great variation possible in traditional Igbo art. Next to the mask by Aka Gworo on the left, (note the mirrors in the eyes) on the right I have placed the same mask made by another Inyi carver, the elderly Ama Dike. The general shape is similar but the coloration is completely different, yet the audience can still tell which character it is. The third picture is of another rendering of the same mask by Ama Dike, who has used yet another painting scheme. This mask remained in Nigeria.

The name of the mask is “una ona”, or ula onu” (depending on which regional dialect). “ula” translates as “to talk bad of you”, and “onu” translates as “mouth”. “When you do bad things, people talk about you in bad ways because of your misbehavior”. This is carried by men aged “26 and up, really strong”. “Just runs, doesn’t dance. Comes to burials and feasts without being invited. If your friend dies and you have a mask, you put it on and express your sympathy by performing the masquerade”. Here is a rare slide of this mask type being worn showing its simple style of costume.

The mask pictured in the Gallery on Page 9, Item 202 has a tongue sticking out and curled horns. My notes say it is named “ana-ahu agu”, translating roughly as “begging the tiger to not misbehave”. This is to dissuade people from misbehaving. It runs around (not dancing) with a whip and makes people scatter!

There is an interesting masquerade in Inyi which is also found in other villages nearby, we were told. However in 1965 it was falling into disuse. It is called “nwanza”, the name of a small yellow bird. I saw one fly one day. It has a pair of extraordinarily long, arching tail feathers, black. These long tail feathers interfere with the smooth flight pattern of a normal bird. This one beats its wings fiercely climbing it up an incline, and then, as if temporarily exhausted, tucks its wings and swoops downward, only to recover and beat its wings upwards again. This scalloped flight path and long, long black arching tail feathers on a bright yellow body make it very interesting to watch, and so, very attractive. I am told early in the morning it sings.

This is a dancing masquerade (as opposed to those that run around and carry a whip). It will have a group of musicians playing “ogene”, (slit gong), “ekwe”, (drum) and “oja”, (whistle). The mask is worn on the top of the head, making it much taller than the crowd. The dancer peers out through openings in the ribbons and fabric below. It sings and dances beautifully. The facial decorations are like “uli” marks on women in the old days. It comes out in October at the Ajaani Festival, and at Xmas. It was suggested that it was once tied to fertility rites, which are disappearing, so it is coming out at other times, like at second burials. “This one usually receives more money in the form of dashes (tips) than the others, because it entertains them more by dancing. What he gets depends on how he dances."

In the Gallery you can see two views of nwanza by Aka Gworo. I find it to be a more intricate and elaborate version. In Enugu I photographed these two examples of nwanza. On the left is Aka Gworo’s, on the right Ama Dike’s. Similar but different. In the Gallery Page10, Items 211 and 211 is another pair made by Ama Dike, of a smaller and simpler size.

Aka Gworo made a great variety of masks, and this is the largest I found. It is a full helmet mask, with a number of items carried on the platform: horns, juju gourds, and birds. It is named “agaba idu”, which can be identified by its teeth, and distorted mouth. It is a very strong masquerade, for very strong young men (to perform). I never got this one out of Nigeria.

This mask is called “agadi mmuo”, an old man’s mask. It is brown in color, which is an unusual color for a mask. Notice the elaborate carving above the head, something which is very difficult for a carver to execute. Here it is photographed on top of a drum at my apartment in Enugu. This is another mask that was left in Nigeria.

The following appears to be another version of a maiden spirit mask by Aka Gworo. It has not been painted. The picture was taken by a PCV who had purchased it, and sent the photo to me years ago. I have no documentation for it.

Other masks by Aka Gworo lack documentation. 1. A round helmet mask with a grotesque mouth. 2. Another round face mask, in his studio, next to a wooden two-tone slit gong. 3. Two black masks photographed at PCV Clarence Hall’s at Ihube-Okigwe.

Here is the only picture I was able to take of Aka Gworo’s workspace. It is very unusual that a carver lets anyone see their “studio”. Mask carvers are making, after all, what is supposed to be secret, i.e., these are spirits, not human, or human danced, so better work in secret in a very private place away from the eyes of the neighbors. The fact that he was comfortable with me taking a few quick snapshots reflects the trust we had developed with one another after doing so many transactions together.

I am happy to say that at Peace Corps Training programs where I worked after I returned to America, I was able to coach the Trainees on how to locate and work with carvers. Many eventually found their way to Aka Gworo in Inyi. This provided him and his family an extension of the extra-income flow I had started for him. I did get some feedback later, that he had raised his prices though! (Good for him!)

Black Masks

Most (not all) of the masks are white, the color symbolizing the spirit world. But a small number of the total masking inventories of a village are black masks. Others have studied these black masks extensively, which you can find in the books in the Reference Section. In general, I have found these black masks to be associated with frightening people, or special burial situations.

Afikpo Village

I found one black mask there. It is photographed here at my apartment in Enugu, sitting on a small triangular table. It has a pronounced rounded forehead, tubular eyes, bulges on the cheeks and sharp teeth. It is designed to scare children, I was told. It is named “okpasu omuruma”, and appears in the Okonkpo masquerade. Another picture can be seen in the Exhibition Catalog Number 22.

Port Harcourt/Elemai Village

Port Harcourt is a port city far south in Igboland, and among the Ogoni and other Niger Delta people. It is a place I have never visited. My good friend PCV Ben Cohen was stationed there, and he sent me a picture of this wonderful mask, with no documentation. It is very large and fits over the head. It obviously has a powerful countenance, maybe even scary.

After my Peace Corps tour I attended Ben’s wedding in Philadelphia, in a lovely park on the banks of the Schuylkill River, one of America’s great centers of the sport of rowing. Many shells were out that sunny day. Ben eventually moved to Montana, and became a powerful State Senator there, championing several environmental laws.

Uzubulu Village, via Onitsha Market

The Obi family of carvers from Uzubulu, often marketed their carvings at the stall on Emejulu Street within the huge Onitsha Market. The first one I found was this striking bat face mask, with a striking red nose and mouth. It is intended for the funeral of a young man. It is named “okpoka”.

Here is some cultural context that I was able to obtain. Half of the Nigerian children in the early 1960’s did not make it to five years of age, and so it had been for decades, maybe centuries. Public health measures and better medicine were beginning to turn the situation around, but, because the high birth rate did not drop, the population of Nigeria exploded, rapidly making it one of the largest nations on the planet!

It was accepted in the culture that death among the very young was “normal” as was death among the elderly. These were viewed as unfortunate but inevitable. The elderly, had survived being babies, had grown into adulthood, probably had children of their own, and lived to old age. That was a completed life cycle, the full circle, and honored, the way it should be.

The death of a teen-ager, however, was viewed as tragic, because that soul had been deprived of adulthood, of marriage, children and the status of being elderly, the cycle broken. In this particular case, in this village, out would come this black mask, the bat mask.

By the way, I shipped this mask to a friend In Ann Arbor, who eventually sold it to a prominent local Doctor Weaver. I have not seen it since but I did take two pictures of it in Enugu, a black and white, and also a color shot which can be seen in the Gallery Page 9, Item 205 for more details.

Also from Uzubulu and the carver Obi, via the Onitsha Market, is this huge black mask. The teeth are painted red, and on the forehead and eyebrows are carved snakes. It is named “akpata”, an “Ekpo” mask, which comes out at the death of an old man, or a feast or even at Xmas, we were told. This one was lost in the trunks in Enugu, during a hasty evacuation.

Another spectacular mask by Obi of Uzubulu is this black panther mask. It is black with bright red teeth and white eyes. The jaw is hinged and can open and shut while being danced, a threatening masquerade if ever there was one! It is also another mask for the funeral of an elderly man.

These masks were carved by Anulugwa Obi of Uzubulu. It was collected on a trip to the Onitsha Market with Kathleen Whitney on February 26, 1966. It is a round face devil mask. We were told: “When old man died it is when it is time of playing”. It is pictured below. A second mask of the same family is shown with snakes above the eyes, and hair attached, named “odogu”, also by Obi of Uzubulu. A similar mask can be seen in the Gallery, Page 10, Item 212. Other masks by Obi of a similar nature are pictured as Items 213 and 214.

That same day we first saw “awuka”, a variety of “agbogho mmuo”, with an orange face and black hair plaits. Secondly we saw a devil face, black, with popping white eyes called “ekwensu” for a feast, but not a funeral, and last, “oji ohu, that had an angel on it, coming out at Xmas only.

Other masks seen that day (but not photographed) included a 3/4 helmet mask by Banafo Obi of Egbama-Uzubulu. It had a pink face, a platform on top sporting two pink and black leopards, and a crest. It was named “kwasi nkwa” and is said to come out at Xmas time.

Also by Obi of Uzubulu is this classic Igbo maiden spirit mask with the high arching horns. It is a type seen around the Awka-Udi area. Notice the typical arching face marks above and below the eyes. The face, in this case, was painted orange. Photographed at my apartment in Enugu, but never survived the evacuation. I was able to purchase a similar “refugee” mask in NYC in the early 1970’s. To see this similar one, visit the Gallery Page 10, Item 215.

Another mask by Obi is this “ulaga” mask, with the long beak. It is worn on the head with the dancer peering through the raffia and ribbons at the neck. The story goes that this type originated in the Niger Delta among the Ijaw people and slowly made its way northwards up the Niger Valley to Onitsha and beyond. It is photographed on a drum head at my apartment and never made it out of Nigeria. The last mask was red in color and obtained at the stall in the Onitsha market. I found no information about it in my notes. It could also come from Uzubulu, but I am uncertain.

Nsugbe Village

From field notes on July 17, 1966: I was with PCV David Conrad, at Nsugbe, a village north of Onitsha. I had seen a few exceptionally well carved statues from there, and they were quite unusual for the time. They were NOT traditional carvings, but rather contemporary carvings of traditional masquerades, a sort of three dimensional photograph. I was able to purchase a small statue of an “ugulu” character for the festival of “Otite” in September, their New Yam Festival. It is only 6-3/8 inches tall and appears in Gallery Page 11, Item 309, and as a field photo below. Also, I was able to obtain an “mmuo” masquerade figure, 26” tall, shown in the Gallery on Page 11, Item 309.

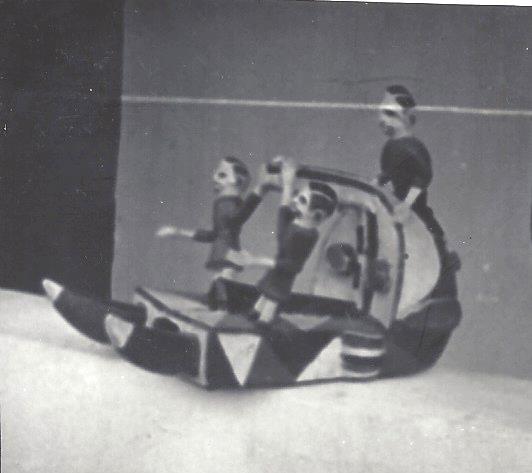

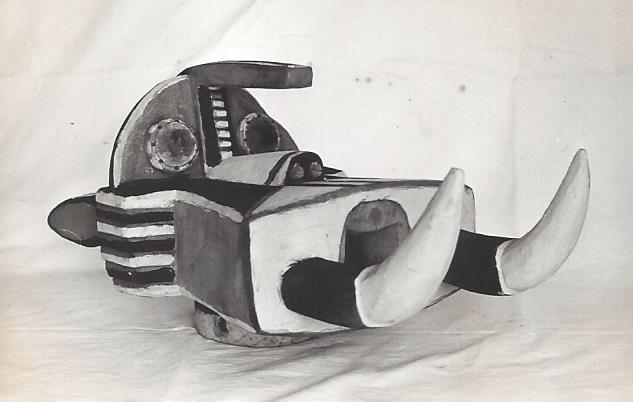

These were carved by Paul Agu. He used modern enamel paints in primary colors (unmixed, right out of the can). He carefully replicated the intricate patterns on the costumes, with as much skill as his carving. He also made elaborate multi-tiered masks for the masquerades, including the Ijele masquerade, commissioned by the Igbo community living in the Muslim North at Kano, Northern Nigeria, at the cost of 80 Nigerian Pounds.

Pictured here (sorry about the poor focus) are images of the “Ugulu” masquerade in action in Nsugbe. One can see the elaborate appliqué fabric patterns on the torso.

From Paul I ordered a large ikenga, measuring 36’ tall. It featured a figure seated on a stool, holding a blade and an “ofo” stick for title. It had a circular platform ‘hat’ containing the usual horns, a spotted bird, and two smaller human figures. This can be seen in the Exhibition Catalog, opposite Number 78. It being so bulky I elected to leave it in Nigeria and donated it to the fledgling Mbari Artists Club in Enugu, 1966, in the custody of the famous painter Uche Okeke.

Nsugbe and the work of Paul Agu was the only place in Igboland where I found a carver rendering images of fully dressed masquerades, rather than, say, just making the head (mask) for the masquerade.

By the way, I once had a carver (in Inyi) curious about the fuss we white people made about his masks. He said: “There are many parts to a masquerade. There are the drummers, guards, dancers, and sometimes singers. There are the members of secret men’s society who wear the costumes. I just make the head. The real artist (he was declaring) is the costume maker: all of that sewing, (most of it appliqué) and weaving (knitting the body clinging suits). There’s the true artist”!

It is interesting how few costumes have ever been collected. I saw one in Europe. I believe it was in a museum in Germany. There was one appliqué costume, folded and buried deep in a drawer at the back of a storage room!

We will present several water colors from Afikpo in a future chapter. These show a local artist’s rendition of the masquerades of his village. Their costume and masking traditions are very different from the other Igbos in such areas as Aba, Owerri, Onitsha and Enugu regions in 1966. I was not able to take many photographs of masquerades. I had a poor camera and the Igbos (then) were scared to death of cameras in case I might steal their souls. It could be dangerous for me as well, as a result. My hat off to Herbert Cole for being able to take so many wonderful colored pictures 10 and 15 years later, which appear in his books.

Abakaliki Province

The Abakaliki area is one far away from Central Igboland, and quite a distance from places that I frequented, such as Onitsha, Inyi, Afikpo, and many cities south On the few visits into that district I learned that the Igbo masking tradition was as strong there as other places, but, often, with very different types of masks.

Ezambo Village

Ezambo is located between Enugu and Abakaliki. At this site was stationed PCV Beckwith. (I believe his first name was Merle.) At his quarters I was able to photograph two versions of masks made out of skin. They were knitted! One was black and the other was much lighter, not white, but light tan. The eyes were highlighted and stood out in strong contrast. Both have pointed caps with hair or fringe in back, around the neck.

I was unable to learn the name of the maker, the mask, or in which events it was played.

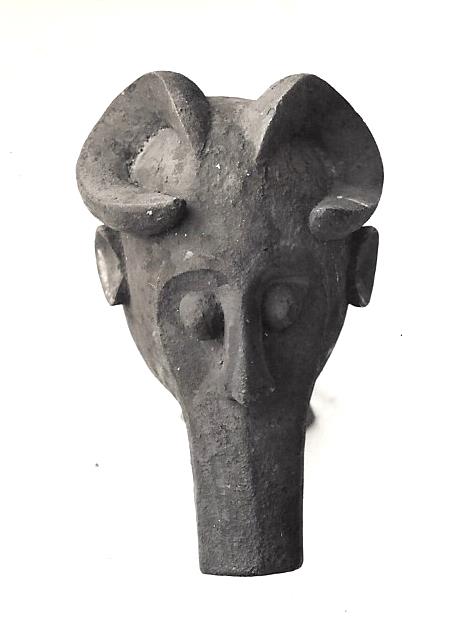

Ogbodo Enyi Masks

This section deals with a rare and unusual mask found only in a small area within Abakaliki Province. In other words, it is not known in the balance of Igboland. The Igbo word for elephant is “enyi”. You can see the tusks represented on the mask. Igboland and most of coastal Nigeria rain forest is now heavily populated. Large wild animals were very rare there by 1966. Elephants in this region have been extinct or killed off decades ago. That doesn’t keep the Igbos from generally being scared to daylights of elephants, even though no one has ever seen one.

This type of mask is worn on the top of the head. It has a massive rounded back of the head. In addition to the prominent tusks, there is a protrusion from the forehead, tubular eyes, sometimes with mirror set inside, and on one, at least, a few human figures.

When I saw my very first “ogbodo enyi” mask, I made a sketch of it. Later, during a visit to Lagos, I was able to share that image with K.C. Murray, Director of the National Museum, and a prestigious old hand in the field of Nigerian Art. He became very excited. He said he had always heard of them, and knew they were quite mysterious, but had never seen one.

I believe this went a long way to relaxing his suspicion that my collecting (which had been brought to his attention, with the attendant suspicions) was of old carvings, not antiquities. Of course they were not old/used, but I was able to bring to his attention someone who was aggressively collecting antiquities for the European trade market. That was against the National Antiquities Act, and he soon sent the National FBI into the field to accost that person. I was left alone. The other guy got away.

(Side Note) It was then that K.C.Murray invited me to donate to the Museum any old, retired pieces that I might come across. This I did several times. I was able to save some old, old ones, carvings that were destined for destruction.

This rare and unusual mask and its use is described at length in the book “ Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos”, by Herbert M. Cole and Chike Aniakor, pages 153-161. There is also a rare color photograph of it in full costume, which you are encouraged to see.

On March 18, 1966 I was visiting the quarters of PCV’s Dunnington and Morgan in Idembia, in Ezza clan, Abakaliki Province. They were both Rural Development PCV’s, in contrast to the rest of us, who were PC Teachers in schools. They worked with local Igbo work crews on a variety of civil construction projects, such as road culverts, and clearing brush for future orchards. Their work was physically demanding, and I always admired their service.

Tom Dunnington collected the “ogbodo enyi” mask he is holding pictured here. We also took additional perspective shots, shown below.

Also pictured are PCV Tom Morgan standing in a nearby yard, and PCV Ron Spaulding standing in a doorway, 1965.

A second mask we photographed at Dunnington’s.

I was able to purchase a new mask, and photographed it on my apartment balcony in Enugu. It was packaged and ready to ship but was lost in the evacuation.

My notes from 1966 indicate the following: This comes out twice a year “for old men” at the November Festival “mumuku” a juju’s name in Idembia Feast”. “Also, there is a second masquerade “ubudegwa’ for young men, that comes out at the same time. A third one, “nwa umumma” doesn’t make as much noise as the rest, stays in one place and dances. It has a carving for a head”. (Not seen, not photographed).

The following text is a direct copy from my notes, which are a transcription word for word in the language of the informant, however different it is from our own version of English.

“Ogbodo enyi” is the most troublesome. It chases women only. Old men can stay around. It will beat and switch you if you get too close. These three are the principal ones to make the juju happy.” “Ogbodo enyi comes out in August (also) when women are ready to be circumcised (?!) The jujus must be informed, so it comes out then, Girls 14-16 years old”. “Law says that no man can marry until he is circumcised, nor have any contact with a woman. The woman will not allow such a man to do that, if she does there are some taboos.”

This is the only time I ever heard of female circumcision in Igboland, and I don’t recall it ever being mentioned in the several books on Igbo ethnography that I have read over the years. I doubt there is any “surgery” going on. I suspect the informant is talking about some sort of rite of passage into womanhood upon her eating from the food resulting from sacrifices from the juju ceremonies.

“Actually the babies (men) are circumcised 8 days after birth, but this ceremony is repeated at 14-16 years. The August festival is for women, right after their “circumcision”. Men are attended to at the same time, but their festival is not until November. Both times the elephant mask comes out.”

I have elected to devote this many photos and story lines to this mask, because it is exceedingly rare, and not many have ever been brought out into public or collected beyond their appearances in the masquerade context. These pictures are over 58 years old, after all. Who knows if it still survives to this day?

Igboko and Neighbors

Igboko is an Aro community located in the northeast of Igboland, in the old Abakaliki Province of 1966. I was told that this community was made up of people from distant Arochuku, who had migrated to this new location some time before. Of course, they brought with them their traditions and their masquerades, which were, in some cases, substantially different from the other Igbo villages nearby.

On May 8, 1966 I visited this location accompanied by Herbert (Skip) Cole, who was beginning his field work leading to his PhD, and eventually his major book “Igbo Art and Cosmos”. His friend Charles Cushman was with us.

At Opafia village at Okoronkwo’s compound we photographed a small doll for children called “nkpata”, which is discussed in the next section on dolls. A similar one was photographed at the compound of Innocent Ikedo, who was acting as our guide and interpreter.

At Usu-enyim, a village near Igboko, we visited the compound of carver Nwonyu. There was a Janus figurehead at his entrance, called Okorompu.

Later in the day we saw an “nwanyi igwe” head statue at Opafia village at Chief Nwodom’s compound. It was also carved by Nwonyu. It has two figures on top, with faces front and back, plus a leopard on top. The front has two faces, one above the other, and another pair on the back. Cole was able to photograph it and it appears on page 154 of his book. My crude field sketch on the left is the wife. There is another mask that comes out called “asufu” that has four faces. It is the man to the wife above. It is a powerful mask, the leader of all masks, and it comes out last.

We were told this is for a number of feasts whose origins are back in Aro: 1.” Ibuna okpabi Feast, 2. Ekpekere Feast is another, 3. Okpuru achi is yet another. The first is in the dry season, around March. The second follows by a week, ie. another four days, and the last at another four days.

I believe Cole was able to get pictures of this troop, but I have been able to find only two such photos in my collection of the funny man type. The first masks in the series are the “oboji” funny man masks.

The second has animal horn shapes, with no special face, called “okoronpu” (the same spelling as another mask photoed earlier) at the carver’s compound, but this is a different one. The third one is a carved crocodile head called “ishiagu iyi, which Cole photographed. It has a skin covered face dark red, with black dots, white eyes, and cam orange at the mouth. There are white rings around the horns. It was sewed to a typical knitted raffia suit with black and tan stripes. The old man, who was the lineage head, said it was carved when he was 6 or seven years old (more than 40 years ago in 1966). My sketch is below.

The fourth, called “asuku”, was a very old example said to have been carved by the grandfather. It had three faces done in native paint. One was black, with a black British pith helmet, another black with a white British Bobby Cap, with a dot between the eyes, at the ears. The third was a white face with a striped chief’s stocking cap, with heavy eye brows, and a dot between the eyes. All faces had slash marks under the eyes, in typical Igbo fashion. All of them had a curious and definite split carved between their two front teeth. This carving was 18’ high. We were told: “These will also come out at funeral, or if a man made a chief (elevated to a higher title) “ he can invite them out for the merriment.”

As an interesting aside, my notes say “The market days in Igboko are named : 1st – igboko, 2nd-ominyi, 3rd-nkwagu, 4th ofoke, 5th-azua. It is the only place I ever found a five day Igbo week. In Aro the 1st is orie, 2nd-afo, 3rd-nkwo, and 4th-eke, the same as the market days in the balance of Igboland.

At Ofiakum village, under Chief Nweme, at the compound of Nwaji, we were told the Nkporum is the headquarters of Ofiakum. There was to be a funeral that day, but it was raining, so the masquerades were not coming out. We were (amazingly) shown the masks in another compound.

1, Oboji- the laughing mask, wearing a fluffy raffia costume. It had red cam eyes. 2&3 were “top of the head” statue masks, women figures with elaborate hair plates. No. 2 – “nyani ala”, (my sketch on the left). No.3 “nwanya ogada “ made by a man who is now a wanderer. It features a large cam red bead at the throat. (My sketch below) There was also a third small face mask, black, with some white, called “nwotaaza”. “He dances with a phallus and chases the other two. (Sketych below). Two other masks were not pictured, named “okoronkpu” and “nwanyi kwonwa” – a woman with a child on the back.

We were also shown their “obodo enyi” mask (of the type shown above many times). This one was attached to a tightly knit raffia suit mainly tan colored, with occasional orange and black stripes. The part around the head was a tan raffia mane. The nostrils of the mask and eye pupils were cam red. The tusks had red yarn wound around them. It “comes out April for general Izi Feast. Every village puts on its own. They told us “every village starts the feast at the same time. It comes out alone; tries to pursue women, hits them (in play, not serious), stick in one hand”.

“Men drum, women dance, mask comes out, women run. People know who is inside from general knowledge. Children remain well behaved and do not run. For a festival common to all Izi. The masquerade collects money from people as it moves by (a standard masquerade behavior).” “All people know the name of the mask. People respect it and don’t tamper with it. It goes home to home. People enjoy the drum and dance, making people feel hot – makes blood hot”.

He says “there is no mask for circumcision festival (16-20 January). General dance in general playground. The Aro people have no masks here. Izi people are said to have bought the “ibina okpabi” from the Aros. The people, when they celebrate it they give a share to the Aros. When they kill a cow at the festival they give a share to the Aros: the hand (the foreleg), an old ceremonial payment for the masquerade. Same for every goat, fowl.”

Finding a masquerade storage trunk was very unusual. Getting the custodian to open it up for photographs was rare. This trunk was from Iboko. The masks were said to be for the funeral play. The two on the right would be worn on the head, making the masquerade bigger and taller than the people around it. The mask on the left is a normal mask, fastened to a fabric hood covering the wearer’s upper body. Before we could get data on each of these masks, an elder approached in anger, (because the secret trunks were being shown at all). Here are two views of the three pieces.

Masquerades in this area that are the most famous are from “ndi ngele’, a big school there. St. Michael’s RCM Primary School. “The masks were carved by men now dead and the masks are very good to look at. The Chiefs and counselors are all rich here. They are Izi people.” Our informant was Innocent Okoro, 28 years of age. He told us he “is a Catholic”.

The following masks were photographed with the assistance of PCV Merle Beckwith who was stationed in the Igboko area. These multifaced masks are common to this area, but quite rare in Central and Northern Igboland. The faces are white or black, with red and yellow accents. They are worn on top of the head making the masquerade quite imposing. Cole has some pictures of these in his book “Igbo Arts – Community and Cosmos”.

This unusual cone shaped mask was photographed at Beckwith’s in his village in the northeast in the Nsukka Region. No documentation was available to us but Cole mentions a few of these cone shaped masks on page136 of his book. It is likely a mask that accompanies the giant and multitiered Ekwe masquerade. This could be one which is “a crowd controlling whipping spirit”, but little detail was available.

Children's Dolls

Children’s dolls are examples of secular carving among the Igbo, along with game boards, doors, and some kola trays.

On April 26, 1966 with Charles Agbasiere, the Chief’s grandson, (and my student), and PCV Tom Tuffs, we visited Oye Village, not far from Ibi and Uli. There we met Samuel Nduaya, who lived in the Ohafia quarter. He had two carved dolls. The first was carved in 1938 (then only 28 years old) and the second in 1944 for his daughters.

They are quite similar to one another, but the newer one is a bit thinner. Both display classical features for this type: beaded necklace, bracelets, beads at the waist, slightly bulging herniated umbilical. They are both slightly bent at the knees, arms at the hips, with wonderful old-style hair plaits. He sold me these two beautiful children’s dolls, which I left in the custody of Igbo arts researcher Herbert Cole for donation to the National Museum, Lagos. They are pictured in the Exhibition Catalog opposite #69.

The next dolls I want to bring to your attention are on Page 11, Items 308 and 309 of the Gallery. These were carved by Onwu Gbucha from Isekke village/Orlu Division, close by Uli. Here they were called “nwa gara oyibo”. Once again we see the bead at the throat, beads at the waist, herniated umbilical area. Here we find the chest scarification, called “mbubu”, indicating readiness for marriage. There is the typical slightly bended knee stance, and a common shape to the feet. The hair plaits are both carved, plus pieces nailed on. In this case, the bodies are tinted orange. The field photo below shows scarification marks on the back as well.

This is a rare male doll by the same carver. The size and body proportions are very similar, but there are no beads or scarification visible. Instead of hair plaits, this boy doll sports a cap! It seems quite plain compared to the decorated girl dolls. This piece was lost in the evacuation.

The next doll was photographed at PCV Beckwith’s in Iboko village, at an Aro compound. At the time I estimated it to be 8-10” tall. It is pictured on the left. There was a second doll which was also about 8-10” tall. This one was purchased by Herbert Cole. It is shown on the right. The photograph is terrible, but you can make out the round head, the extra long neck. By blowing up the size on my copy machine I was able to make out the typical bend at the knees, chunky legs, the hands held at the waist, and the neck covered with many rings of beads., all features found in our previous examples, and the location of this village is a hundred miles from the previous two!

The following is a lengthy story about me and an Igbo doll. I hope you enjoy it.

I had a lot of wonderful experiences in Nigeria. I was living among the Igbo, learning something new about their culture, which I got to know quite well by the time came for me to leave. The following is one of the most remarkable things that has ever happened to me, anywhere.

The Igbo Doll: The Background Story

My first Peace Corps assignment was at the Uli Boys Secondary School, originally living with the Principal/Headmaster Father Ned D’Arcy, an Irishman belonging to the Holy Ghost Fathers. He had a comfortable little cottage with a spare bedroom where I stayed. It didn’t take very many days for me to figure out that this would/could not be a long term situation. I needed my own place to stay, and the only way I could solve that problem was to build myself a house.

The school was still young, with only two Forms (classes), amounting to 60 students. It was just now allowed to bring in a class (30 more students) because it finally got a graduate on the faculty (me). That meant tuition revenue from 30 more families, but they had to build another class room block, and expand the dormitory. There was no money for faculty housing yet. It was operating on such a thin budget they were not about to build one, anytime soon, at least.

After weighing all of the alternatives, the only way was to build one myself. I would not do the day-to-day physical construction work, but I would design it, lay it out, dig the shallow foundation, select the cement block and other materials from commercial sources, and act as the construction manager. All this on a Peace Corps salary of 75 Nigerian Pounds per month (valued at about $2.40 per pound in US money). This salary rate was set on the basis of housing being supplied by the host, and the balance to go for groceries, a cook-steward employee to prepare the meals, and a little spending money, which would include travel money (taxi’s, buses, etc). By being able to room and board with Fr. D’Arcy I was able to save a little that way, and move the process along faster.

I soon became friends with the block mason and other workmen. When school was done in the afternoon, I would join them on the site working side-by-side with them. It was as new for them working with a person from a very different culture as it was for me. They were honest and hardworking, and I could tell they appreciated my own hands-on involvement. My relationship with them was different from the one they had with the Father, and different from the one I had with the Father, too.

Once the house was completed enough for me to move in, I began to acquire more and more masks, statues and pottery, lying about, which was definitely noticed by the folks. One day, returning from my class room (a brief walk from the other side of campus) I spotted a gunny sack hanging from my door knob. Within it was a wooden carving. It was not a shrine figure, it was secular. It was a children’s doll, a girl.

I soon learned who gifted it to me, and where it came from, being the village of Ibi, so close by. One of my workmen lived there, and was aware of my growing appreciation of Igbo art. As the story goes, the lady who had this as a child had passed, and it was sort of “in limbo”. My workman friend knew where it would get a good home and brought it to me. It was a wonderful and unexpected gift. I learned that the woman’s father had carved it for her, and had carved a second one also, for her sister, when she came along.

It was one of the most “pure” Igbo designs I ever found. The body and legs are a bit on the chubby side. There are wonderful hair plaits on top, a large bead at the throat, indicating birth into a high status family. There are classical beads around the waist, and bracelets around the biceps’. The hands lay across the belly, stopping at the typical bulging, herniated umbilical area.

On her back was a pair of body scarifications, one on each shoulder, with a rounded shape tapering to a point at each end (like an American football). The legs are slightly bent at the knee, so common on Igbo sculptures in the Central Region. The patina was dark brown. The bottom of the feet had been sawn back, just a small amount to remove degradation from years of standing on the Nigerian soil.

This piece taught me that Igbo wood carving also had a secular side, in addition to spiritual/”juju” purposes. I will share some of these other secular pieces below.

I brought the doll with me to America, and because it was my favorite, I often displayed it in my residence with my ikenga, while the other masks and statues remained in the trunks for all those years.

The story now fast-forwards two to three years. I had returned to Ann Arbor, and changed my unfinished PhD studies in Economic Development to Cultural Anthropology (which I never finished). I was able to organize an exhibition of my collection at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA), and publish a 64 page catalog. This is available electronically on the home page above (Yellow Cover). In it you can see pictures of “the doll”, Image #69. On the opposite page is a pair of dolls from the Village of Oye, which I collected and sent to the National Museum, Lagos via the researcher Herbert Cole. They were carved by the father in 1938 and 1944, respectively for his two daughters. Many of the features are similar, even though Oye is over 60 miles from Ibi, (and Isekke, the village of the other orange dolls).

By this time the Nigerian War was raging, and hundreds, if not thousands of Igbo art pieces were making their way to Europe and America. These were pieces stripped out of the shrines and men’s lodges, spoils of war. They were sent off through the international African art distribution system (without any provenance, of course).

My Exhibition catalog became valuable to gallery owners in such places as New York City. With it they were able to assign certain background information to the host of pieces they were marketing. As I learned of this I started to visit New York from Ann Arbor nearly every weekend! (sixteen weekends in a row at one point). Looking over the pieces flooding in was both an exciting and a sad experience for me. I could interpret the degree of devastation that was sweeping across Igboland as the war was lost, a little more each month.

One Saturday I arrived in NYC and headed to my favorite primitive art shop. It was a place that had always been open and friendly to me. I would identify pieces for them, as best I could, and they would give me a fair price on Igbo pieces I wanted to buy. As a a struggling graduate student there was only a tiny budget for such things. Those pieces purchased in New York are labeled as such and can be found in the Gallery above.

As I approached the shop that morning I decided to pause to see what was in the front window, something I did not usually do. I was struck speechless at what I saw. Slowly gathering my composure I went inside the store and brushed my way past the new clerk (who didn’t know me) and went straight to the back office. The owner was sitting at his desk and was delighted to see me.

Immediately I said,” There is a piece in your front window, and I own it now. I have no money to buy it, but I will make you a trade, piece for piece”. I opened my catalog and dropped it on his desk. “Any piece, any page there; put your finger on it and it is yours. Even trade, any piece.”

He paused for a moment to consider that offer, and slowly began flipping through the picture pages. He stopped and put his finger on a woodpecker mask from Afikpo. And I said,” Done!” (I breathed an internal sigh of relief, knowing I still had another back home.)

Whatever would make me give such an offer? What was it that had stopped me in my tracks? It was the missing sister doll; the sister to the one the workmen gave me years before from Ibi!

Feature by feature, I can go through the whole list. They are the same! The size, the stance, the bracelets and beads, the hand placement, the umbilical mound, the color. The only difference is the way the hair plaits are presented. The newly found one did not have the twisted cones of curving hair like the first. On this second doll there is a sharp solid crest to which ribbons and yarn bits had been tacked, not carved, but still decorated in the historic way. Only the tack holes remained.

The missing sister, found on a spring morning in New York City.

I could have arrived a week before and it would not have been in the window. I could have arrived a week later and it could have been sold away. I could have walked directly into the shop and not bothered to look at the front window and missed it. No other Peace Corps Volunteers familiar with Igbo art, or any college professor of African Art could have seen that piece and realized the connection. I was the only one who could, and I did.

It remains to this day, one of the most remarkable coincidences I have ever experienced. Maybe, I was still in tune with something I had absorbed among the carvers of Igboland. The one given to me in Nigeria is on the left. The one I found in NYC is on the right.

Igbo Doors

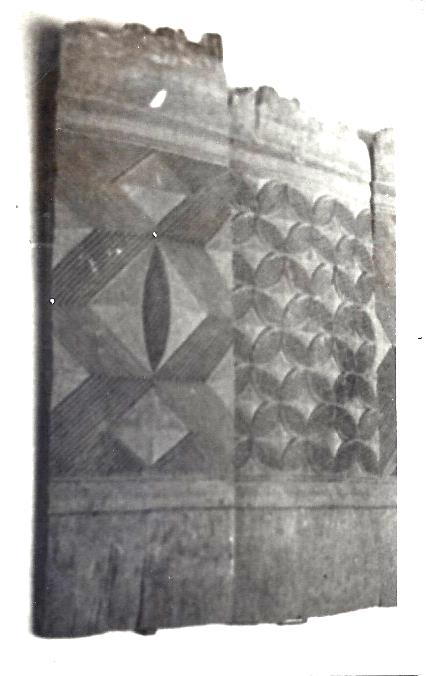

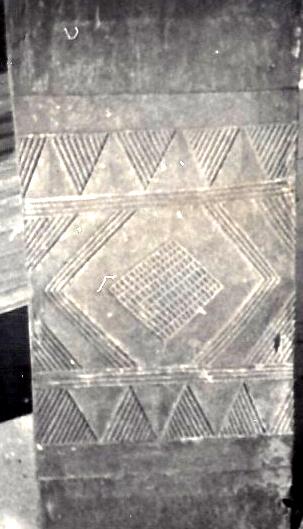

Igbo doors are commonly carved with fascinating geometric patterns. Please see the Exhibition Catalog above, opposite #59, and #67 and # 68 for more description. In 1965-66 many indigenous mud-wall dwellings were being replaced with European style cement block homes, requiring doors much taller. In the USA the conventional height is 6’-8”, for instance.

These older doors, typically around 4’ in height, were being cast aside, thrown into a junk pile, and eventually burned! I was able to capture some images from time to time. I apologize for the poor camera work. When scanning I have used the brightness and contrast adjustments to improve the clarity somewhat. I want to show the wonderful and varied designs patterns.

The first group below was photographed at the National Museum, Lagos in 1965. They had a substantial collection already and didn’t really need hundreds more brought to them.

PCV Bill Shurtleff, a teacher in Okigwe, appreciated these wonderful designs and had gathered some at his school where we were able to take these pictures.

These first two designs came from Inyi where I was able to purchase the never-used huge door set shown in the Exhibition Catalog #69, and in the Gallery, Page 26, Item 505. The last door is from Ibi, the village where the sister dolls came from. It was photographed at my apartment balcony in Enugu, but never made it out of Nigeria.

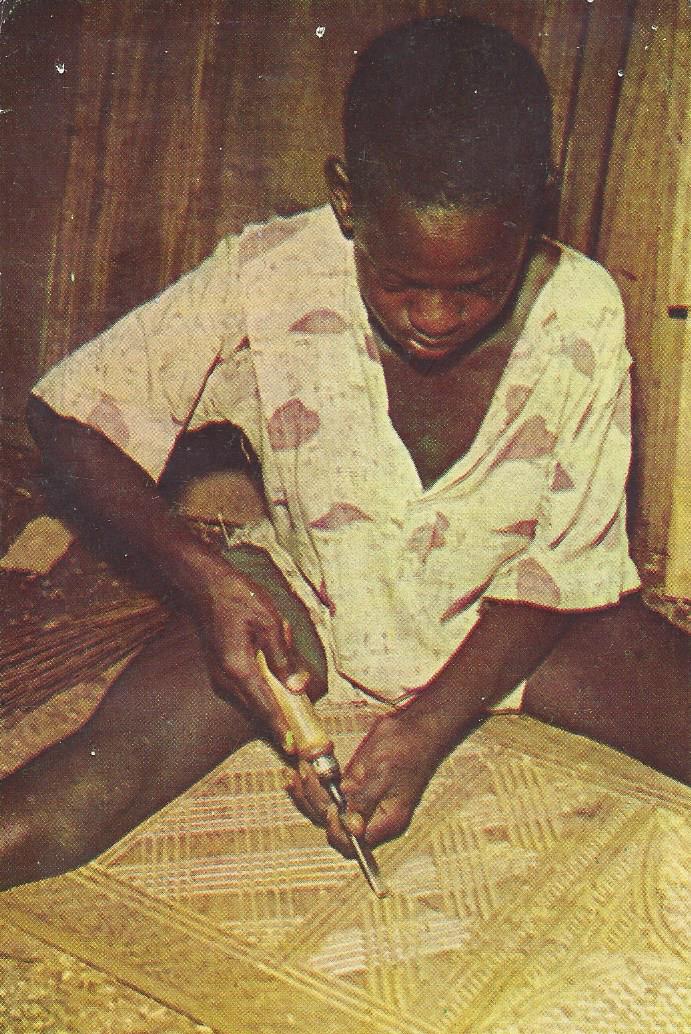

Awka

Many of these wonderful geometric designs were being kept alive by the Awka Carvers Co-operative, which was thriving at the time. Awka has historically been a center for traditional Igbo art and ceremony. Pictured below is a postcard showing a young man working on the endless number of intersecting grooves which are so typical of this style. The back of the postcard has the following identification: “Lagos. International Trade Fair 1964, Awka carver. Invest in Eastern Nigeria”.

At Awka patterns are carved for display as panels in desk fronts, for doors of the “modern” height on special order, and for trays. One tray I purchased there in 1966 is shown below.

Here is a large door-set for a new contemporary house being delivered for installation. A small number of wealthy businessmen and prominent political figures elected to have such traditional patterns displayed to demonstrate their respect for the traditional culture at a time when so much was changing so fast.

Igbo Drums and other Musical Instruments

I found the Igbo people to be very musical, especially at their great dancing exhibitions and during masquerades. Their drums were always made of wood, and had a skin head on one end only, unlike typical Yoruba “talking drums” from the Western region, that had skins on both top and bottom. Some of the drums, especially standing ceremonial drums, had carved decorations. A few retired ones are pictured below. Some were “fat”, and some were long and narrow, like the one from Inyi that appears in several pictures above where I used it as a prop for photographing masks.

At a ceremony to celebrate the awarding of a chieftaincy to a “big man”, I saw a professional drumming group from a distant village hired for the special occasion. They had a variety of drum sizes, and many had surface decorations. They are pictured in action below.

Another popular percussion instrument was the wooden slit gong, of various sizes, and therefore, of various pitches. A piece of special hardwood is used. I do not know the name of the tree, but “iroko” is a good guess, as it is very dense and heavy, (like White Oak is in America). A section of log was hollowed out creating a large internal resonating space, and two sounding panels, opposite the central slit. One panel is carefully carved a bit bigger and thicker than the other, resulting in two distinct tones.

The Igbo language is a two tone language. Gifted slit gong players can actually beat out a pattern of high and low notes/tones that many people can recognize as words, and phrases, being their own form of talking drums. These two-tone slit gongs were very popular, and their sound could often be heard at a distance greater than the drums.

Igbo researcher Herbert Cole and I visited Azumini village one day. There we found these two splendid ceremonial Igbo drums. They were retired from their service as age-grade drums. Those would be drums specially carved for an age-grade, which would be regularly used, year by year, as long as the age-grade society stayed in tack. They originally had skinheads, but were no longer in service. Both have figures carved in bold relief, and stood on stool-like legs. This means that the drummer would be stationary, as opposed to the more common walk-around drums carried with a sling at the hip. The notes on the back of the field pictures indicate that these were collected by Herbert Cole for the National Museum, Lagos.

I apologize for the poor quality of the photos from my cheap little camera of the day, but I felt it was better to include them to show the layout of the figures. A different design is the tall, narrow drum used as a prop in this photo of a statue. It was about four feet tall and had an unusual high pitch.

Elsewhere I found two other wooden drums, which I sketched. The first was from Ishiagu, best known for its pottery. This is a short, squat drum of good diameter, which stood on short legs. The notes say its name is “ekete”. It appears on the left. On the right is a sketch of a drum at Okpoha/Afikpo Region, several miles east of Ishiagu. My notes have two names written next to it: ”abia” and “nkwa."

Yet the designs are very similar. Notice how the drum head is stretched over the top and down the sides a short distance. Their thongs run vertically from the head down to a strap around the body. For tightening and tuning, small wedges are driven in behind the strap. Because both of these are quite wide, and have short feet, I do not believe they were carried around on the hip, like some others, but rather set upon the ground and played from there.

Besides drums and slit gongs in 1965, the Igbos had other types of instruments as well. Here are a few more that I found.

The first is a calabash gourd, quite hollow and dry, decorated with a network of beads, called “achacha”. It is shaken or bumped against the hip or the opposite hand. My sketch from Okpoha/Afikpo Region is on the left. A second percussion instrument is the “oha”, which is filled with seeds or pebbles and shaken by hand. It is shown on the right.

The Igbos love a kind of metal bell that is commonly heard during masquerades and at dances. This one, from Okpoha is called “ogele”, but in other places to the west it is called “ogene”. In some cases, it is fabricated with two sounding bells, of slightly different pitches, which can be used like the slit gong to pound out a two toned word, phrase or message. This one was part of the Udi Professional Drumming Group hired to put on a show in Inyi.

Next is an instrument I never heard of before I came to Nigeria. It is a pot for making a musical note. It is round in shape with an extended neck. A leather patch is smacked on the hole on the side and a sound comes rushing out of the top! It is quite muffled however, and is easily covered over by the loud drums. The sketch on the left shows such a pot from Okpoha, called “ite” there, but is known as “udu” in other parts of Igboland, where I found them, such as at Ishiagu, pictured in the Pottery Section above. The second sketch on the right shows a smaller version from Akagbe quarter of Okpoha. It is a bit smaller than the drum version. The player places his lips on the hole and blows in it as if playing a bugle. A loud note comes blasting out of the top! This creates yet another one note rhythm voice.

Other Instruments

I am sure I heard some flutes or whistles during dance exhibitions or masquerades, but I cannot find anything in my notes on them. I have no photo or sketch to offer.

The last instrument I am reporting on is much more complex, and quite rare. Imagine a wooden xylophone, which we may know as a marimba. The only one I found was in Okpoha/Afikpo,and I commissioned one to be built for me. The sounding boards come from a tree called “ulo” which is “very scarce and has nine leaves”. The instrument‘s name there is “egbelegbele”. Twelve to thirteen sounding boards can be installed, each a little bigger and thicker to determine its pitch.

They usually would drill across each panel in two spots making it possible to string the assembly together as shown in the sketch. This keeps them in order and eliminates the time wasted by sorting out the sizes every time it gets set up for performance. The sounding boards are placed on the tree trunks of two banana trees. These unusual trees appear to be fleshy green sheets of pulpwood wrapped around and around a core. This as opposed to the ring-upon-ring annual type of tree growth we are familiar with. It is very fleshy, and does not interfere with the resonating boards. These are typically played by three musicians. One is placed in the center, and the other two are to the left and right, but on the opposite side. They strike with mallets, creating a wonderful soft pattern, often rhythmic, like a conventional percussion instrument, but in this case, a melodic line can also be carried.

It took a long time for the builders to find all of the proper pieces, and get it assembled. I took delivery and hauled it back to my apartment in Enugu. It being so long and bulky, therefore hard to pack and crate, I was never able to get it out of Nigeria, lost in the evacuation.

A Game Board