Sculptures

Traditional arts in Igboland take many forms, as the Gallery collection demonstrates. Perhaps the most epic in sculpture design are the shrine figures. The biggest can be quite lengthy creations, like five or six feet tall. These would typically be found in major shrines devoted to an entire village, whose population, in some cases, can number in the thousands. Somewhat shorter shrine pieces, such as two or three feet in height, might be in one of the neighborhoods or divisional sections of a village. Other smaller figures might be found in family-wide compounds. Examples of these different sizes are presented in the following field photos and in the Gallery collection.

I found in 1964 that traditional Igbo shrines were (1) going out of style, (2) no longer being taken care of due to their degradation, or (3) threatened by missionary programs.

When I first moved to Eziama-Uli Boys Secondary School, I lived with the principal, Father Ned D'Arcy, an Irish Priest from the Holy Ghost Fathers. From him, I learned about Guinness Stout, ice cubes in my beer ("We heard you Yanks like your beer chilled."), the Irish sport hurling, which games were broadcast by the BBC radio station, and what to do on Friday nights. The options were to go to the movies (shown on a sheet strung up somewhere) or the shrine burning. Local people were being recruited to demonstrate their newfound Christianity by burning/destroying their historic "pagan" shrines. This was in 1964, a full four years after Nigerian Independence!

By 1965, I was no longer stationed at the Uli Boys School. I had become the English Language Officer for the Eastern Nigeria Ministry of Education/Enugu, with a Jeep station wagon for field visits.

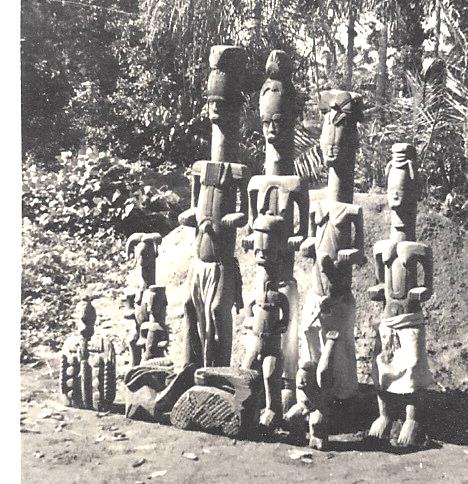

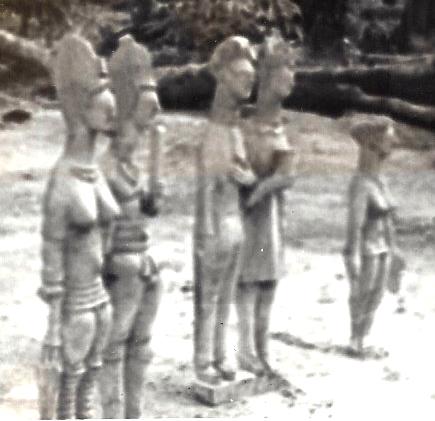

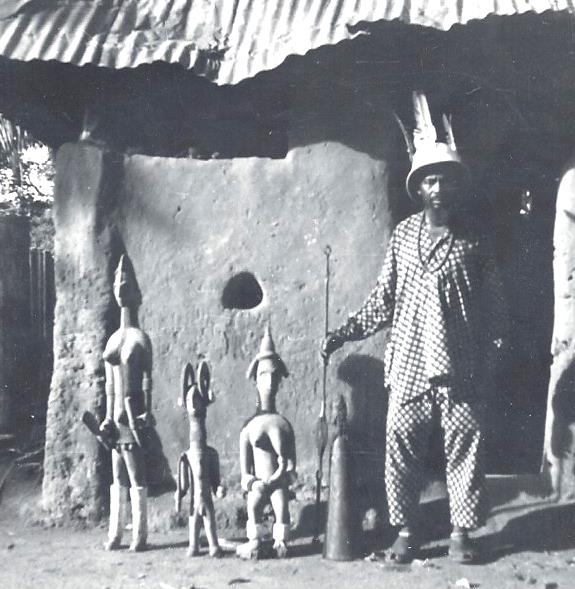

One day, out in the field, I had just completed a day of training a PCV teacher in better English language teaching methods at their school. Leaving that village along a dirt road, I came upon one of the most amazing things I ever saw in Igboland, or in Nigeria, for that matter. The village was having the thatch roof replaced for their major shrine. The workmen had stood the ancestor statues alongside the road in the sun. It was rare to come upon a full-size shrine not being readied for the fire pit but having its roof repaired for another lengthy period of use protected from the elements. I happened to have a camera with me (a better one, this time) and I was able to take these shots quickly.

I took the following notes, but now (50+ years later), I realize that I did not record the village name, perhaps to protect it from becoming a target of the shrine burners. Unfortunately, the information I was able to collect hastily from the workmen was limited. First, they were startled when a white man stopped his car to show interest. Second, they were very uneasy when I got out my camera. A few greetings in my imperfect Igbo language and some praise for the figures relaxed them a bit, but the sun was going down, and I was still more than an hour from Enugu. So, my time and their patience were limited.

They told me the tall male figure (far left) is named "Ezealaogaku", or alternately "Ezealaogugo". They told me (quote), "These two (including the wife next to him) have got sons and daughters (gods and goddesses) who have become gods and goddesses of smaller areas." They said the shorter male figure (third from the left, third tallest) is "the prince, who will take the place of the Ezealaogaku", and therefore "his leg must not touch the ground until he takes over (?!)". "He sometimes demands things that his father does not like to give him, like having a beautiful girl sacrificed to him. This young one can cause much trouble by sending out the father's counselors to do his deeds. He can dry up the Mba River for two to three weeks until the priest can discover what is wrong."

The short girl (fourth on the left, back row) is a very kind one (as opposed to the young man). She loves her brother very much and cannot do anything about it when he does wrong. She is the goddess of women and responsible for having beautiful girls. These two (somewhat shorter) tall one's control areas in the Father's area of power. The animal is the boy's platform so that he does not touch the ground!.

That was all the information I was given. I'm sorry, but there is not more, such as the names and functions of the shorter pieces. I was lucky to come upon this once-in-a-lifetime chance.

Other examples of the taller type are shown by these six photographs taken at the residence of Peace Corps Volunteer Janet TerVeen in Ikeduru. They are of a classical and elegant Igbo style, which is prominent in that vicinity: Elongated faces, long necks, similar treatment of the arms, lengthy bodies, and thick legs. Some have patterned forehead scarification, ichi, and a series of scarifications down the chest, mbubu. Some show commonly seen herniated umbilicals as well. Examples of this type appear in the Gallery on Page 15, Items 354 and 355.

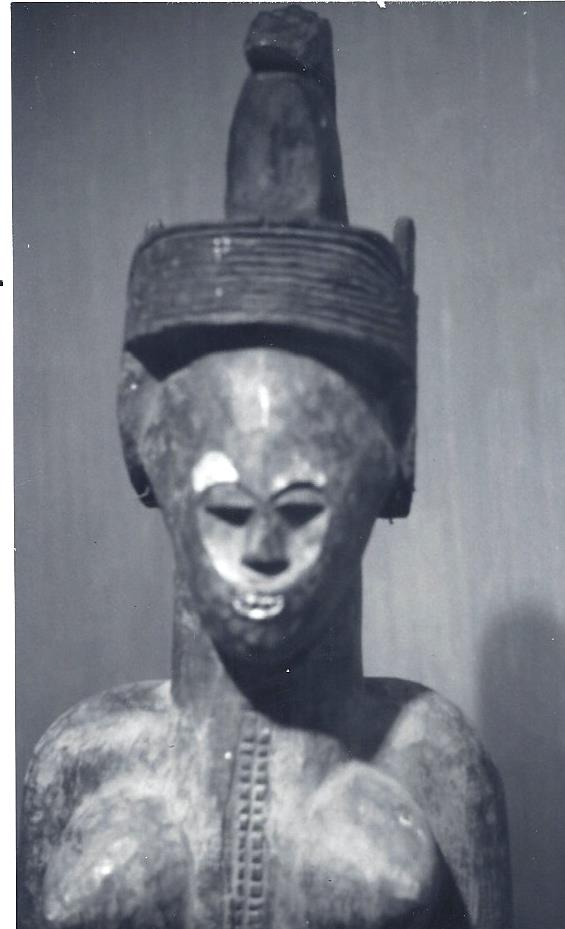

Other pieces are the ones shown here, photographed at the National Museum Lagos in 1964, and two views of a female figure photographed at the Detroit Art Institute in February 1971. A similar female piece is shown in the Gallery on Page 11, Item 301, from the Awka area. The two-colored pictures were taken in David Ackley's studio, Ann Arbor, in the 1960s and show a style prominent in SE Igboland.

Examples of the medium-sized shrine figures are shown here in Awha-Oye, along with the carver Samuel. These are well-crafted pieces done in a style completely different from those above. Once again, we find the dominant male holding a staff of authority on the left. Next to him is the female figure wearing the traditional beads at the neck, wrist and waist. Both have an ancient and elaborate hairstyle built up in a crest. Variations of this crested hairstyle appear on many maiden spirit masks and other statues. The shortest one must be the daughter.

Upon closer examination with a magnifying glass, the tall pair on the right appears to be a couple in European dress! The man appears to be wearing shoes, slacks, a shirt, and even spectacles. The woman appears to be wearing a dress with a knee-length skirt. Both are holding a book to their bosom. Could these be Bibles, and is this an Igbo depiction of missionaries? It is a mystery.

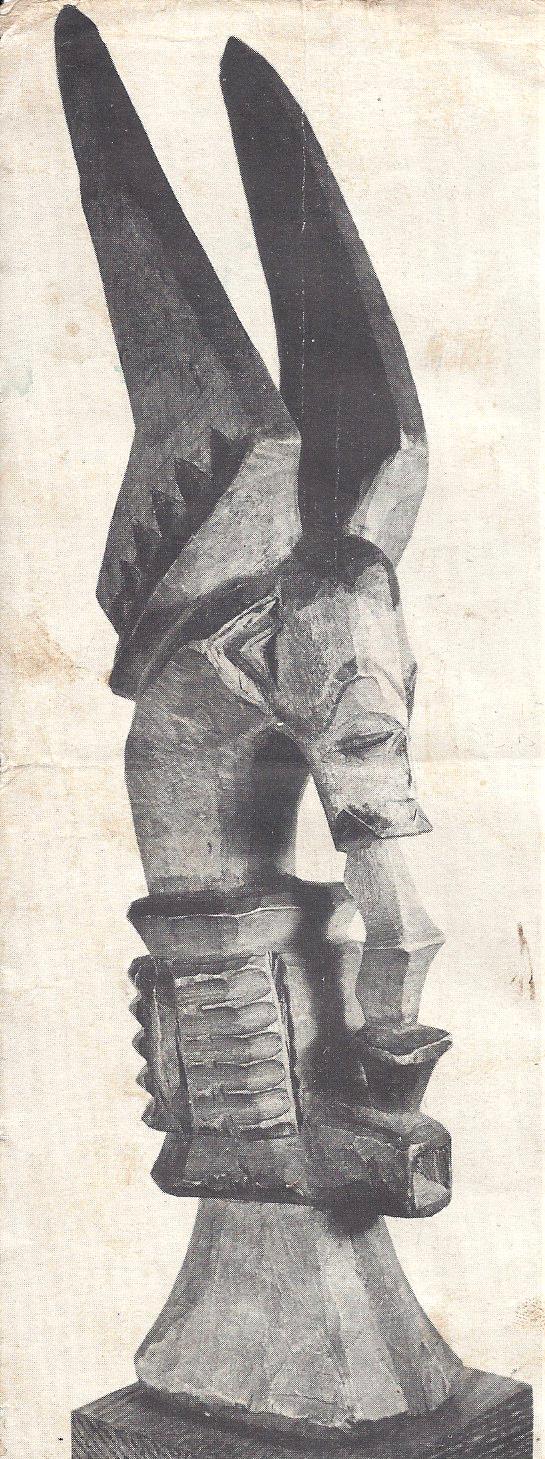

In yet another style, we have this shrine figure carved by Njoku at the Oriagu market area. It is a more rectangular and "blocky" type of rendering. It was photographed by PCV Science Teacher Bill Shurtleff, serving in Okigwe. Bill and I made several collection trips together. After his Peace Corps service, he lived in Yoruba country, collecting a volume of carvings, which he sent home to California. The funds he raised from their sale were used for scholarships for his former pupils at Okigwe. Bill and I met again in Boston in 1967, where we worked together on the Peace Corps Nigeria Training staff.

Shorter ancestor figures in yet another style were photographed at Umunumo, near the Oriagu Market, south of Okigwe. This style lacks the refinery of the types shown above. I believe the carver is proudly holding one of the pieces in one shot. I did not get his name. I did obtain five pieces of his work. In the picture with three statues, I was able to bring out the one on the left and the right. They can be seen in the Gallery on Page 15, Items 354 and 355. The other ones were packaged and readied to be sent out but never appeared because the Civil War broke out. Many things were left behind when the evacuation came upon the Peace Corps and other USAID workers, including four trunks making up the other half of my collection scheduled to come out with other people's shipping allotments, but they were never seen again.

Shrine Stories from Inyi

Inyi was probably my favorite place to visit in Igboland, with the gigantic Onitsha Market a close second. I had a number of wonderful experiences there, all related to my interest in the arts of the Igbo. Come with me as we go to Inyi village.

Because I had the Jeep station wagon at my disposal (right-hand drive in Nigeria), I could visit a wide area and often did so on the weekends. Now, the week in the Western world, as well as the cities and schools of Nigeria, is seven days. But in the villages of Igboland, there are only four days a week. They are called Afaw (usually spelled Afor, like the "aw" sound the British pronounce in the word "doctor."), Orie, Eke, and Ngwo, or Nkwo.

By the way, I can go to any American phone book and find Igbos, because of the naming pattern they use with the word "Oko": one who is born on….day". So, you get Okafor, Okeke, Okorie, and Okonkwo by the dozens.

Each village has a market day, and the neighboring villages have a different market day. Some markets specialize in meat/live animals (goats and chickens), palm wine, or certain vegetables like yams. Now, all the markets may have some of those products to offer, but there are some that have much larger selections. So, a shopper may have to walk a few extra miles to get what they want on a given day, but they can get it.

Peace Corps volunteers knew these market days well, and so did their cook-stewards, who did the grocery shopping for the household. Market days are days of great activity and liveliness. The local "law" is that everyone must put in an appearance. Often, the old men would find a favorite area under a shaded roof and drink palm wine as they commented on the people walking by, keeping up on the latest news. Believe me, the "bush telegraph" was much faster than the Nigerian Postal Service. News could get around lightning fast, like when this red-bearded young white guy appeared in their midst.

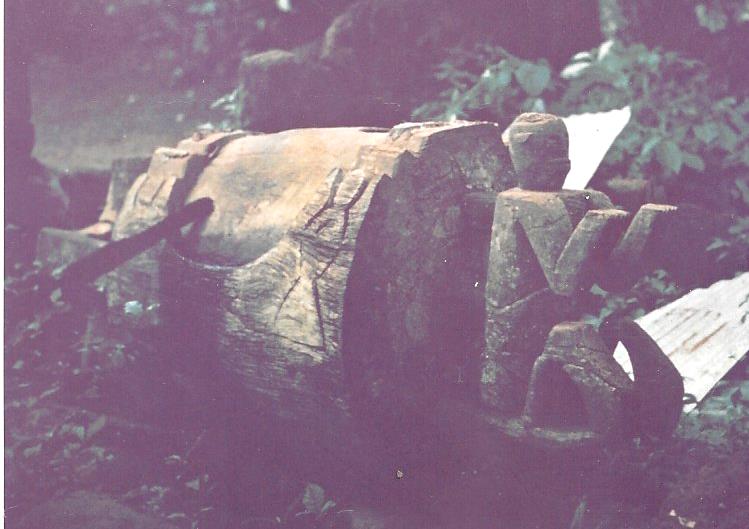

One day, I drove into the central area of Inyi, which was adjacent to the market. Walking around, I spotted a rare and wonderful ikoro drum under a small palm frond roof. I had heard about these, but I believe this was the first one I ever saw. I was drawn like a magnet.

It is not really a drum, in the usual sense—a cylinder covered at one or two ends with skin for sounding or drumming. These ikoro are carved out of a huge diameter tree trunk from the ikoro hardwood tree, I believe. This is the same wood used for making the carved doors found everywhere at that time, but they were gradually phased out as they went to the taller 6'-8" doors that we are used to. The ikoro is more of a giant wooden gong.

As I understand it, these functioned as signaling devices since they could be heard at great distances. In Scotland, playing certain tunes on bagpipes from the hilltop served as similar signaling devices. In my hometown in Mid-Michigan, the bells in the County Building Tower would serve the same purpose. Today, we have sirens and giant loudspeakers to warn us of tornados and bad storms. In 1965, Inyi still had the ikoro, probably the last generation of them.

The immense tree trunk (3-4' in diameter) was hollowed out, with great effort, removing a huge volume of wood down deep inside through a narrow slit at the top. How could the arms and tools be managed to do all of that work through such a narrow slot? On each side of the top of this giant log, a pair of flat-sounding panels were created. One was left with a greater bulk than the other, offering two distinct tones.

Now, here comes the genius. The Igbo language is a two-tone language. There is a high tone and a low tone. Sometimes, a final high tone will fall off to a mid-tone, but let's not make this more complicated than it is already. Say the word with one set of tones, and it has a meaning. Say it with a different set of tones, the same word, and it will have a totally different meaning! Change the tone; you change the word. This is something outside the life experience of English speakers. It is complex and hard for us to hear, let alone generate, and presents the central challenge for Peace Corps Volunteers working in the villages to overcome. It didn't bother the USAID (foreign aid workers or the Embassy staff) because they dealt exclusively in English and just struggled with the Nigerian version of English.

The player of the ikoro is able to hit the lower sound panel with a stick for one tone, and the higher tone panel with a different stick for the other tone. To those who knew the patterns, a particular series of high-low tones actually spoke the language they could understand. I can recall learning how to play the bugle as a Boy Scout. There was one tune for mess call, others for reveille, or raising the flag. My favorite was a tattoo; we can all recognize taps when it is played. Any soldier can tell which one is sounding. It is a four or five-tone communication system. The Igbos did it with only two.

I ducked under the low palm frond roof and marveled at the relief carvings on the giant gong. Of course, I couldn't resist, and not knowing any better, I softly tapped the sounding panels with the end of my finger. Their tone was clean and clear. So impressive. This thing was decades old in the African weather (rain, heat, humidity) and still had tonal integrity. (Later, the carver, Aka Gworotold, told me he was the person who carved it! He said Ngele Ebelebe is the name of the god for whom it is carved.)

What I wasn't prepared for was the sudden appearance of a man out of breath and highly agitated before me. His eyes circled around and around in their sockets. Oh, Oh! I could be in trouble here! He came straight up to me and pressed his bearded face right up against my bearded face. Eyeball to eyeball. I got the full power of his stare. Then I felt his hand slowly climbing up my shirt front and into my red beard, and he gave my beard a good feel. All the while, our eyes were locked together, nose to nose.

Well, I said to myself, in the folkways of this village, this must be the way this man offers his greetings, so I reached up into his beard and gave him a good feel, too. As unorthodox and even daring as my response was, I had apparently made the right move. I was not intimidated, and his demeanor relaxed. As he stepped back, he pointed to the ikoro and asked if I was the one who touched it. I gave him a greeting in my beginning Igbo (which he never expected to hear from a white man) and said yes in Igbo. So he learned that this was not a village emergency that had been signaled but that a white stranger had blundered into touching something that everyone else knew was never to be touched, except in emergencies.

I soon learned that he was also in charge of the adjacent shrine. When I asked if I could see inside, he cautiously agreed. He became more comfortable as I openly admired the sculptures in my limited Igbo language. I asked about some by Igbo names (ikenga, etc.), and he was learning that I was not a threat and even appreciative. I did not get his name, but we would meet again.

Later that day, I found my elementary school teacher friend at the market. He spoke good English, was a citizen of the village, and had sound status there. I used him as my translator. We went to the compound of the oldest carver there, named Ama Dike, an elderly and somewhat small-sized man and an immensely talented carver who learned his design craft from earlier generations. We had met many times before, and he sold me several wonderful (newly carved) masks. I told him I had been to the shrine and how beautiful the figures were. He seemed to appreciate that and replied that he had carved most of them years ago. I told him I saw a tall female statue, about "this high," which was holding a paddle with ivory bracelets on her long legs. He broke in to say proudly, "I carved that many years ago." The weather was mild and pleasant. We were comfortable and pleased to see one another.

Right before me, a remarkable opportunity had just presented itself. I recognized it at once and decided to act on it. Gathering my courage, I began my series of questions, hoping to string together a series of affirmative responses. "You carved that woman figure?" Yes, he nodded. I sat quietly in contemplation and appreciation. I said, "It was you?" "Yes," he acknowledged. Followed by my further quietness and appreciation. "You made that?" I asked again. "Yes, of course," he replied. Another pause, followed by, "Can you still make one of those today?" He had to think about that for a moment, replaying in his mind the steps and effort required. "Yes, I can," he finally said. Then, summoning all my courage, I asked, "Can you make one for me?" His eyes blinked. He paused again for a moment, reflecting on how much work it would be, for it had been several years since he had made the last, and how unusual it would be to make one for an outsider. After he took time to contemplate all that, he swallowed and finally said, "Yes, I can." Understand, I had already purchased many pieces from him over the previous months. He knew I was a good customer. Once more, I brought him several Peace Corps Volunteers in recent weeks, who became enthusiastic customers as well. Our relationship benefitted him, and he appreciated it.

Being an elderly man, his capacity to tend to vegetable patches and yam plots was diminished. Cash was hard to come by, and yet, unexpectedly, scarce money began to flow to him for doing something he was good at and loved to do. And a lot of that was because of me. We had developed a fondness for one another, and our divination kola nut ceremony was manifesting true when we first met. It told us, "Our meeting will benefit us both." And so, it did.

But this last question of mine was surprising to him. He trusted me, but this would be the first time anyone (outside the Secret Men's Society) had asked him to make a traditional shrine figure. The request had not come in the full cultural context from a fellow villager or even a fellow Nigerian but from a white man! (A Peace Corps Volunteer, no less!) Obviously, the next question would be his compensation. Within his culture, he would be paid with an extensive annuity of vegetables and baskets of foodstuff flowing to him periodically over several months. Obviously, in this case, it would have to be exclusively cash money, the same as all our previous transactions for masks.

I finally asked him, "How much would you need?" He named a price much bigger than those of any mask (of course, as expected). It is respectful to pause and contemplate his number. I soon responded with a slightly lower figure (of course, as he expected). If I had accepted his price straight off, he would have immediately and unhappily concluded that he had asked far too little. That would make him unhappy and undermine his enthusiasm for the project. I did not want that to happen, so I did observe the custom of negotiating but did respond with a figure that was not much lower than his initial offer, one he could easily accept in good faith. He agreed.

I later learned that part of the compensation package had not been translated by my elementary school friend. He figured I learned a few months ahead that he would go back and talk the carver out of that part, but he forgot, and I bumped into the issue when the carving was ready for pickup. That story is just ahead.

With the amount decided upon, I gave him a substantial cash down payment to demonstrate how serious I was about paying for the balance when it was completed. He smiled and shook my hand in acceptance.

Then, I thought it would be important to get more specific about my expectations to head off any future differences of opinion. Some carvers had delivered masks I had ordered painted with modern enamel paint. I wanted the old traditional paint only. That was O.K. with him. Some pieces had shown up finished with all kinds of goofy things painted on them. Once, a different carver told me he was trying to please by making it pretty in the eyes of the white people. The carver had seen some chintz patterns on some British kitchen curtains and concluded that that was the white man's aesthetic. And so that carver put his recollection (as best he could) of such designs on the mask where they didn't belong!

I didn't want British designs on her body, but only those old ones, like the original statue. They are called "uli." He agreed to that as well. I believe somewhere I spotted a study done by a scholar who recorded many of these "uli" designs and explained their meaning. In ancient times, they were used extensively for body decoration, probably during an era when the Igbo women did not cover so much of their bodies with garments.

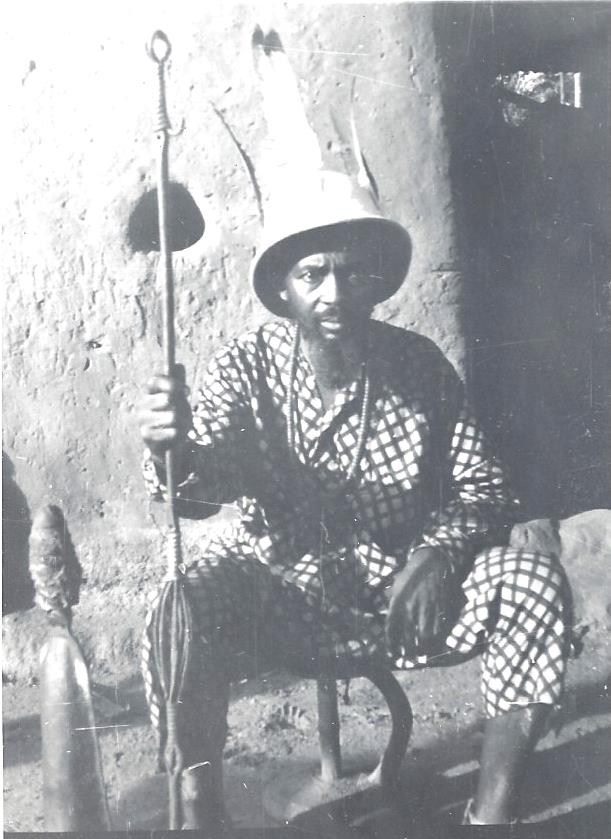

A few weeks later, I returned to Inyi to pay respects to Ama Dike and give him a little more money on the transaction. That day, we were able to meet the shrine priest (the man whom I had met so unexpectedly at the ikoro sounding). We convinced him to bring out some of the shrine pieces for a photograph. He proudly presented himself for a portrait with his staff of authority, metal-sounding gong, and hat with feathers while sitting on his ceremonial stool.

The second picture shows him posing at the entrance to the shrine with three shrine figures. On the far left is the subject female statue carved by Ama Dike so many years ago, the copy of which he was making for me at the time. The central figure with horns, holding a blade, is an ikenga. The one on the right is another female ancestor statue, a daughter figure. We did not get pictures of any other statues within the shrine, just the ones he wanted to show to us.

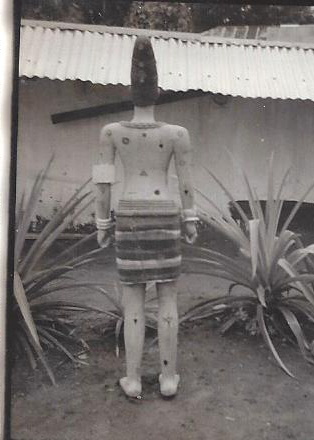

That same day as I paid Ama Dike some additional money, he brought the partially finished statue out from his home to demonstrate how much progress he had made. My apologies for the poor focal quality of the picture. The carver is the short man on the right.

Some weeks later, the time came to pay the balance owed and collect the finished piece. I brought the local schoolteacher as a translator to ensure everything went smoothly. Ama Dike gladly took the balance and showed me the statue.

It was dyed a pale yellow with dark blue-black dye on the hair and the fascinating body markings. He explained that my request for a traditional paint and "uli" had set something unusual (and unexpected) in motion in the village. He had to find old women who knew not only the body marking designs but also where to get the dyes. There would be dyes made from this leaf, that berry, this root. The word got around quickly in the quest for knowledge of the dye sources.

This, in turn, brought young girls of the village into their effort. These girls had never seen such body markings once used several generations earlier. I can imagine them asking, "What did they mean, and where did the dyes come from? I never knew you could make a color from crushing that leaf." Etc. Almost like a quilting bee in our own culture (a once common event now nearly disappeared), the young girls gathered around when the oldest ladies, the oldest keepers of a near-extinct historic body painting style, carefully, precisely painted the new ancestor female statue.

I venture to say that if I hadn't thought to request the traditional dyes and "uli," those teenage girls would never have seen the body designs so universal amongst the generation of their great-grandmothers. Double-checking my notes in 2024, I see that the name for this type of idol in Inyi is "Aja-ala." Ama Dike charged me an extra five shillings for the lady "uli" painter.

There was just one last "little" problem, though. It was with the compensation. Ama Dike balked at releasing the statue. "What was the hold-up?" I asked through my elementary school teacher translator. The balance of the money had been paid. What was the matter? The schoolteacher replied sheepishly, "The goat, Sir." "What goat?" I shot back. "Every shrine figure must have a goat as part of the payment!" "What?" I exclaimed. "I was never told this." The schoolteacher said, "Oh, yes, I remember Ama Dike telling me that when we were finalizing the sum, but I never paid any attention to it. I planned on talking him out of it later, but I forgot to do so." To which I said, "So now, I am supposed to produce a goat?" "Yes, Sir!"

Luckily, it was market day. There had to be a goat for sale there somewhere. I had parked my Jeep close to Ama Dike's house, more than a quarter mile from the market. I couldn't imagine putting a goat inside the back of the Jeep, thrashing around as I drove the distance from the market to the statue. How would I explain the certain interior damage to the Jeep to the USAID station and to the Peace Corps Director? If put off until another day, who knows if the statue would still be there when I came back 2-3 weeks later, tardy on my payment? I had to collect it that very day, or never. The process had come too far, too smoothly, to have it fall apart at the last possible moment. Not for just a goat! So, I decided to jog the quarter mile back to the village market. It turned out it was more like one-half mile!

West African dwarf goats are short, stocky little critters and wander all over the place. They climb and prance and chew and scatter about. They are not the tan, long-legged goats with long floppy ears that the Hausa people sometimes bring down from the north, the Nubian goats that resemble an Irish Setter dog but with tan coats. Nope. These goats in Igboland are sturdy, vigorous little animals. The ones pregnant with twins (most commonly) carry an unborn kid on each side of their bellies, looking like side saddles on a roller skate. A typical such goat is pictured here.

I was lucky to find a few for sale in the late market and to have a few pound notes left in my pocket after paying off Ama Dike. The negotiation for a goat in the market by a white man was as much a new experience for me as it was for the seller of the goat. I selected an all-white one, and not having a clue what the fair market price was and being a bit anxious (easy for the seller to detect), I'm sure I paid too much for it. Too bad for me. I was after that statue!

Igbo men will hog-tie a goat and unceremoniously lash it on top of the rear fender of their bicycles to get it where they want it. I had no bicycle. My Jeep was a half mile away. I wasn't about to pick it up and carry the heavy, squirmy thing because the moment it wriggled away from me, it would "cut-for-bush," and I would never be able to catch it. There would go my goat, there would go my statue, and there would go my money, too!

I was reminded of the time, back in the States, when I also had a short, vigorous, and stocky white animal in my life. It was my English bulldog, named Socrates. With that dog, I had a collar and a leash. Why not do that here? What would work for the bulldog would certainly work for a dwarf goat! I quickly bought some rope, fashioned a collar with my Boy Scout knots, and got it around the goat's neck despite plenty of resistance. The market-goers were beginning to take notice and gathered around to get a better look at what the young white man was doing. I tied the rope leash to the collar and tried to head back the half mile to Ama Dike's compound, walking the goat like a dog. The goat wasn't having any of it. It bolted left, pulling me off balance, and fell to its knees at the end of the rope. I yanked it back towards me, and it bolted off to the right, looking over its shoulder at me, scared to death. I stumbled but didn't fall.

The goat and I supplied quite a lot of excitement in Inyi that day. The gathering crowd of Igbo market-goers roared in laughter at this crazy white man trying to walk a goat on a leash. Why didn't the guy just bash it in the head, knock it out, and carry it away? Like the Pied Piper of Hamlin, I marched and zigzagged down the road, careening left and right like a water skier, the village kids following the whole way, laughing and leaping for joy at the fun.

I finally made it to Ama Dike's, the goat much tired out and me breathless. He took the goat, with a curious expression, then smiled and was cordial as we loaded the statue in my Jeep. As I drove through the market, I beeped the horn and everyone waved and smiled. Plenty to talk about in Inyi that night.

Back in Enugu, at my upstairs apartment, I was able to take some photographs of the decorated lady on the balcony. The pictures here clearly show the uli markings. Item #71 in my University of Michigan Exhibition Catalog (attached above) shows the original older statue by Ama Dike, positioned next to his new one I collected in 1966. Detailed information about her features and jewelry are covered there.

The story doesn't end there. A few months later, it was time for me to leave Nigeria. I had purchased several large and locally made steel trunks in the Onitsha market to ship things back to America. They were painted black, with hundreds of small red shapes repeated back and forth across the surfaces. Into them I was able to place many masks and statues, which appear in the Gallery of the collection. The Peace Corps would pay for only a certain amount, which in this case was five trunks. A sixth we shipped to Spellman College in Atlanta, for show-and-tell teaching purposes at the upcoming PC Training program in which I was going to work. It was the summer of 1966. The collection I have today is still packed in those six trunks, stored in Bay City, Michigan.

I packed several Ishiagu pots, additional masks, and more divination pieces in the three other black trunks. The Inyi female statue by Ama Dike was far too big and tall to fit into any trunk. I had no choice but to leave her behind, even after the entire saga of obtaining her. There had to be another way. I decided to cut her in two, which I did, in order to fit her into the space available. I figured I could always piece her together again in the USA. After all, it was the cultural and sculptural aspects that were the most important.

Since the Peace Corps limited our shipping allowance, I had to find another way to get them home. In Enugu, I became good friends with a USAID (US Aide for International Development) officer. He had unlimited shipping. When he and his wife came to Nigeria, they brought their whole household, including the entire dining room set with them— tables, chairs, buffet, and side tables, which they were planning to take home with them at the end of their tour in another fifteen months or so. They generously agreed to include my extra trunks with their things, so I put them in their garage. Wherever they end up in the USA, I could arrange for further shipping to me, or I could collect them in my future station wagon.

However, after I had gone (May 1966), and before their term was up, the Nigerian-Biafran Civil War broke out (1967). The Peace Corps Volunteers were evacuated by road and by sea, which itself makes for an amazing group of individual stories. It was pretty much a situation of drop and run. Many things were left behind. My USAID friend and family bolted eastward into the neighboring country of the Cameroons, leaving behind their household furniture and my trunks, including the trunk containing the lady by Ama Dike!

I traveled from Ann Arbor, Michigan, several times to New York City over the next two years. I found dozens of Igbo shrine statues and masks that had been stripped by the invading army and sold into the international African art network showing up in the stores. Many went to the capital of Europe, and many came to the USA, primarily, but not exclusively, New York. I visited many tribal arts shops, looking over the Igbo art flooding in from the war, hoping to find any of my original pieces. I was able to supply some shop owners with mask names and even likely the village of origin based on my own travels. But I never found one of my missing pieces, and I never found the lady by Ama Dike. But I did come across something remarkable, which I will share in another story coming up.

The Chief's Statues

The following is a story about another tall female figure I found, pictured below. Chief Gregory Agbasiere lived in Eziama-Uli. He was the current Vice-Chairman of the Eastern Nigeria House of Chiefs in the government of the day, a man with considerable political power. He was also a major player in the Catholic community. It was through his efforts that the (Catholic) Uli Boys Secondary School was created on village land not far from his compound. He was a very large man, compared to most Igbo men, and he was also warm and compassionate.

He was very pleased to meet me as the first college graduate to join the staff of "his school." Having a graduate on staff was necessary for the school to become accredited by the government. These new, young schools added a class of about 30 each year, and this would be this school's third year. A new classroom block would be built each year, a one-story affair with shutter windows on each side, with an open trestle roof supporting corrugated metal roof material. This was called "Bam-Bam" in the local pidgin language, reflecting the fact that it often made a lot of noise when it rained. In fact, a classroom conversation often became impossible if the rain was too intense. A dorm room was also added, as these students lived at the school, and none lived at home and walked to class.

In order to obtain a school, a large piece of land needed to be assembled. The Igbo settlement areas were quite dense, with houses and vital vegetable gardens adjacent. To assemble a large campus required removing dozens of families from their traditional Igbo home sites. This would result in those families losing their self-sufficiency, which was extremely important to them. They had to find housing elsewhere, but in exchange, the men folk were given guaranteed wage jobs at the school. These subsistence farmers were now becoming construction and maintenance workers.

The Chief had a large two-story cement block house built for him with a large yard. I was able to take these photographs of the traditional statues he displayed at the entrance. It always seemed a little unusual to me that such a powerful Catholic man should still have ancestor shrine figures about.

Writing today, I wonder if the Chief was keeping the statues from the shrine safe, which had been demolished as part of the land acquisition for the campus. Not destroying them may have been a politically necessary compromise after seizing so much of his neighbor's land for his project, the school.

Of greatest interest to me was the tall female figure since it resembles so closely the figure carved for me by Ama Dike of Inyi, more than 50 miles away. The female figure shares the following similar features: large, built-up hair, necklace, elephant ivory jewelry, and uli markings. In this case, the "uli shapes are much reduced in size, almost appearing as dots, but a variety of designs are revealed under a magnifying glass. I am uncertain about the figure with the sword raised above his head and the one on the left. The garment details on the two figures on either side of the female I never saw on any other traditional Igbo carving.

I read in one of the very early publications on the Igbo that the Uli area had poorly developed traditions of wood carving. In 1964, it was very difficult to find any Uli carvers, but with the help of one of the Chief's sons, a student of mine, he was able to find a divination set for me, but I don't remember meeting the carver. Its design is simple, and its execution is of lower quality. It makes me doubt that these very large figures were carved by any local Uli carver. I am almost certain that they had been obtained years ago from some outside source.

Western Igbo

Most of the Igbo settlements are east of the mighty Niger River, but not all. There are also a handful of Igbo villages on the western side. The biggest is Asaba, featuring the ferry dock directly opposite the huge and bustling Onitsha. I traveled through this western Igbo territory every time I went to Benin City, which lay on the far side of the Igbo, but I never had the time or inclination to dig into their traditional arts like I did on the eastern side of the Niger. I did once, however, stop in Kwale and take these poor-quality pictures inside a shrine. One can make out some shorter statues there, but the remarkable stacked carving, displaying several individual figures, is prominent. I never saw such a stacked shrine piece on the eastern side of the Niger.

Ikenga

The end result of my research was a bibliography of 640 entries. In 1968, at the back of my University of Michigan Exhibition Catalog, I repeated the exercise focusing solely on Igbo articles at that time. You can find that at the end pages of the Catalog attached above.

I remember buying a cheap paperback book on African art at the time, which was long on photos and short on documentation and content. From that particular 1960 era book (title long forgotten) I detached the page on Igbo. Each side showed a picture of an ikenga. I took that page with me to Nigeria. The pictures are below. I knew that Igbos had sculptures. I had seen a few pictures in the library books. I could also tell they were not widely collected or written about.

When I got to Nigeria, I asked Peace Corps Volunteers and foreign aid workers about Igbo carvings, and they all told me there were none. The PCV teachers were most commonly focused on their schools, and did not hang out in the villages all that much, in part, due to their poor training in the Igbo (or Pidgin) language. I realized that many of them had not come in contact with that deeper level of the traditional culture.

Undeterred, I began to ask "the folks", my local Igbo neighbors. Universally they would deny such things. Uli was a strong catholic area, and admitting knowledge of things "juju" was not wise for them to do. They were mostly conditioned to deny the pagan, especially to white folks, who might make a big fuss about it.

After a week or so of getting adjusted to living with the Irish Father, I was able to get a ride with a neighboring PCV into Onitsha, maybe 30 miles to the north. I took my page with the ikengas pictured on it and showed it to random men in the huge market area. I was surprised to find that many of them had little experience looking at picture images, not understanding what they were looking at, often turning the page upside down to try to decipher it. When I said "ikenga" though, they realized that I knew what I was talking about, and that soon led me to a stall, deep in the market. There they were. A half dozen or so small statues were sitting on a table. I purchased the first one I saw. I still own it today. It is my ikenga. It is pictured here and sits on a shelf next to my computer today.

I returned to that stall many times over a year and a half, becoming friends with the vendor and learning more about who carved some of those things, including my ikenga. From time to time, there would also be divination figures of great variety and, rarely, a mask.

Ikenga is a statue seen in almost every corner of Igboland, except Afikpo region. The Igala people, living north of the Igbo are said to have the ikenga tradition as well. The name is made up of two words: i-ke (pronounced EE-keh) meaning strong/strength, and "n-ga" [pronounced nn-ga], meaning place. Ikenga=Strong -place. refers to the right arm of a man. The larger statues offer a man holding a blade, usually shaped like a machete. If a man has a strong right arm, he has a good life force. He can achieve success and become self-reliant. He is able to make his way in the world. I heard that when a man died, the right arm of his statue was cut off, symbolizing the end of his life force.

The most common feature of an ikenga is its two horns. A more extensive description of ikengas is shown in the Exhibition catalog, and images of the various sizes are Nos. 78, 82, 85, 91, and 93. The full academic investigation of ikenga has been done by J. S. Boston, whose book is listed in the Reference Section above. My Gallery shows dozens of various ikengas of different sizes on Pages 12-14, 18-19, and 21-22.

Here is a picture taken at my apartment in Enugu where I set up a row of different small, personal ikengas, just to demonstrate the amazing variation offered by the individual carvers. On the left, one found at the market stall in the Onitsha Market, no data; second, an ikenga from Ozubulu, by carver Obi; third, an ikenga from Eziama-Uli; fourth, an ikenga from Uke, purchased in the Onitsha Market; fifth, an ikenga carved by Chukuegu from Mbaise; 6-7-8, all purchased in the Onitsha Market, carvers unknown. The tall one was photographed at PCV's Dunning and Morgan quarters in Abakaliki Province. They said it came from the Awka area, many miles away. It is the only one I ever saw that had a carrying handle through the horns.